Kristin Hay

Admitting Women Series: Part three

Part Four / Part Two / Part One

Kristin Hay is a medical historian and a doctoral research intern at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. She is currently working on the ‘Admitting Women’ project which explores gender inequality within the College’s history as part of the Heritage and Inclusion Programme.

By the end of the nineteenth century, women had been able to become medical practitioners for almost 25 years. Female physicians and surgeons were increasingly entered into the medical register through various portals of entry, including the Conjoint Diploma offered by the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow alongside the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons of Edinburgh. The Universities (Scotland) Bill of 1889 enabled universities to draw up Regulations for the instruction and graduation of female students; thus from 1893 women were also graduating in Medicine from the University of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Having successfully ‘re-entered’ into the profession, the next hurdle facing women in medicine was in advancing their career progression.

Although women were able to become physicians and surgeons, there were still nonetheless considerable institutional barriers in place to limit women’s ability to make a viable career in medicine in Britain. In order to progress into more senior positions, such as teaching posts or roles within hospitals, practitioners usually had to have recognisable post-registrable qualifications, such as fellowship to the Royal Colleges and other medical authorities. Yet, as discussed previously, female fellowship was considered a vexed issue within the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, with members remaining significantly hostile to female medical practitioners. In 1892, the topic had been raised at a Faculty meeting, but at that time it was considered ‘inexpedient’ to discuss, given that no women had even requested to be submitted to the Fellowship of the Faculty. [1] However, in 1896 that changed as Elizabeth Adelaide Baker, of Oxford, applied to be considered as a Candidate to the Fellowship – sending shockwaves through the Faculty and its members.

[Credit: C. Baker. Photo generously submitted to us through the family of Dr Baker (c. 1920s)]

Baker was born in South Africa in 1871 and was registered through the Triple Qualification (TQ) in 1892 having been educated at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, founded by Sophia Jex-Blake in 1886. She was one of only 80 women who received a medical education there. [2] As she had passed the TQ, Baker was thus a Licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow as well as the Royal Colleges of Physicians and of Surgeons in Edinburgh. Consequently, Baker was a legacy of the Faculty’s examinations and representative of its role in enabling women to practice medicine. Despite this, Baker was refused entry to the Fellowship by the College, based on a minor legal technicality within the Medical Amendment Act of 1876 which only permitted women entry into so-called ‘registrable qualifications.’ [3] As the Fellowship was theoretically a post-registrable qualification, the Faculty decided that they could not be open the fellow’s examination to women.

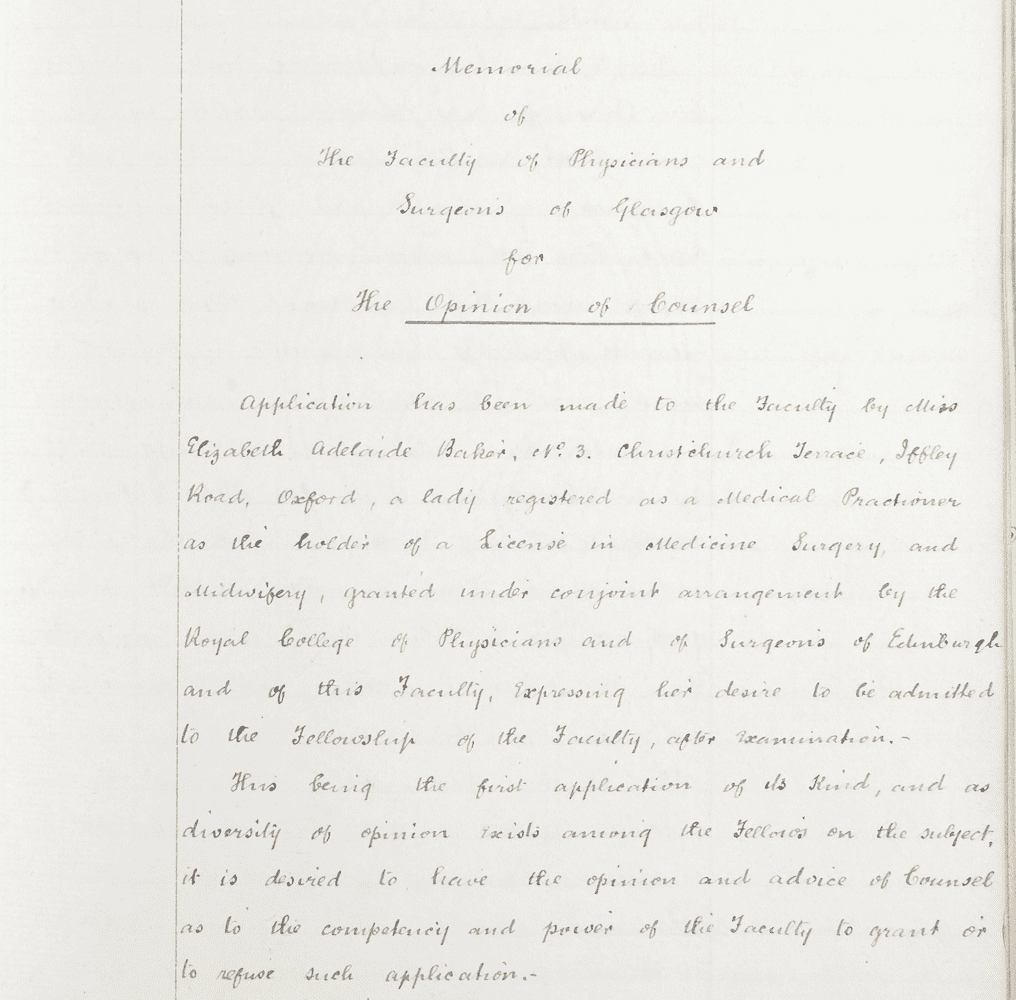

Although using legislation as a justification for their refusal of Baker (and thus absolving them of responsibility), the Faculty had previously noted itself that there was ‘no legal incompetency on the part of the Faculty to admit Women as Fellows.’ [4] Thus, it was clear from the outset that the Faculty had very little interest in permitting women to the fellowship and so actively sought ways to legitimise their pre-determined position. Indeed, a twenty-page Memorial seeking the Opinion of Counsel was created in view of ascertaining the powers of Faculty to admit women as Fellows, in which they themselves revealed the ambiguities surrounding the legality of female fellowship. Enlisting the support of lawyers, then, was a means to interpret the law in their favour.

Within the Faculty’s memorial to Counsel, intended to be an objective and balanced document, further clues to the Faculty’s point of view emerge which highlights again the use of tradition and legacy in preserving the identity of the Faculty and its members. While admitting that the original Charter (quoted at length in the text) made no reference to women, the Faculty nonetheless argued that the use of the words ‘brethren’ and ‘gentlemen’ hinted towards their exclusion from medical practice. [5] They also considered the duties of Fellows to be ‘masculine’ and made reference to the manner in which women had historically engaged with the Faculty, stating that:

‘In the original Charter [it is] clearly indicative of the male sex as being those alone concerned with the privileges and duties conferred or devolved on the Faculty.- at the same time it has to be mentioned that the records of the Faculty bear evidence that…cognisance was not infrequently taken of female practitioners, but in such cases it was to inhibit or discharge them from practicing.’

‘Memorial of Faculty as to the Opinion of Counsel’ (1897)

In making this comparison, the Faculty thus presented female practitioners in the past as unregulated and illicit, omitting that a great number of medical men were also prohibited from practicing by the Faculty at this time. The Faculty continued to indicate their opposition to female fellows, arguing that:

‘When in last century, the Faculty instituted and Examination for Midwives…In no instance does it appear that the women, so accredited, received other benefit, privilege or freedom, or in any way became members or, as they ultimately designated “Fellows” of Faculty.’ [6]

‘Memorial of Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow for the Opinion of Counsel’ (1897)

This shows that the Faculty saw their history and legacy as a potential means of justifying their continued exclusion of women from the inner-circle of their medical community. The fact that they had not admitted women before was considered one way in which they upheld the traditions and values of the Faculty itself. Indeed, the Faculty further cited other examples where tradition and regulations prevented women’s admission to medicine – specifically the case of Sophia Jex-Blake and the University of Edinburgh which was decided in the institutions favour. Consequently, the Faculty’s counsel ultimately agreed with the view of the Faculty, commenting that:

‘The terms of the original Charter appear to as to exclude the view that women could competently have been admitted to the rights and duties of those persons whom the “Fellows” of modern days represent…Women, while no doubt they might be entitled upon examination…were not eligible among the “brethren”.’ [7]

‘Opinion of Counsel,’ JB Balfour and David Dundas (1897)

The steps taken by the Faculty to justify their refusal to admit women as Fellows emphasises the enduring hostility towards female medical practitioners in the late-nineteenth century and the institutional barriers that women continued to face in the pursuit of medicine. The narrow reading of the law and the emphasis placed on archaic gendered language shows the deep-rooted sexism within the Faculty and the ways in which they sought to preserve their identity as exclusively male. It is also notable the ways in which tradition and heritage became tools in which to justify their inaction and absolve them of responsibility.

Elizabeth Adelaide Baker continued her practice in Oxford before moving to Sheffield and then East London, and passed away in 1928. [8] While ultimately refused, Baker’s attempt at obtaining Fellowship to the Faculty represented a further push for gender equality in medicine. As we shall see in the post to follow, she would not be the last woman to seek fellowship, but rather the first in what would quickly become a movement that the Faculty would find increasingly difficult to ignore.

If you are interested in learning more about the ‘Admitting Women’ project and the history of gender equality within the College, our next ‘Reframed’ virtual event takes place on Thursday 27th of May from 6 PM. Details and registration information can be found here.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

[1] RCPSG, GB 250 1/1/1/11, Faculty Minutes, ‘Admission of Women to the Fellowship’ (2nd May 1892) p. 528

[2] J.M. Somerville, ‘Dr Sophia Jex-Blake and the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, 1886-1898’ Journal of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh 35 (2005) p. 266

[3] RCPSG, GB 250 1/1/1/12, Faculty Minutes, ‘Memorial of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow for The Opinion of the Counsel’, (1 March 1897) p. 166

[4] Ibid, p. 175

[5] Ibid, p. 168

[6] Ibid, pp. 173-174

[7] Ibid, p. 177

[8] We are grateful to the family of Dr Elizabeth Adelaide Baker and especially her great-nephew Mr Christopher J. Baker for generously consulting on this blog post and providing a detailed history of her life and her work.

Leave a Reply