Kristin Hay

Admitting Women Series

Part Four / Part Three / Part Two

Kristin Hay is a medical historian and a doctoral research intern at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. She is currently working on the ‘Admitting Women’ project which explores gender inequality within the College’s history as part of the Heritage and Inclusion Programme.

The nineteenth century was a pivotal period for medical practitioners in Britain. After centuries of professional struggle and attempts to legitimise the profession, the 1858 Medical Act formally distinguished highly-trained physicians and surgeons from unqualified ‘irregular’ practitioners and created an educational, legislative standard for entry into the medical profession. Through the creation of the Medical Register, practitioners were required to hold a licence to practice medicine, granted by the universities or through the recognised medical corporations, such as the then-titled Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Since its incorporation in 1599, the Faculty had raised the standard of medical practice in the West of Scotland by examining practitioners and prohibiting illicit activities. As such, the Medical Act represented the culmination of centuries of professional regulation by the Faculty and its members.

However, as the Medical Act debarred quacks and itinerant practitioners from entry to the Medical Register, it simultaneously delegitimised a number of highly-skilled female practitioners by limiting access to medical education and practice. While women healers were not an uncommon feature in both urban and rural communities throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the Medical Act reduced portals of entry to the medical profession by requiring Candidates to be examined only within the universities and corporations– the vast majority of which were not open to women. Despite the pioneering efforts of individuals such as Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson – both of whom brilliantly obtained medical licences by exploiting loopholes within the system – and the protests of Sophia Jex-Blake and the infamous Edinburgh Seven, it would not be until an Act of Parliament in 1876 when women would be able to legally obtain a “registrable” qualification. Yet, although women were finally able to receive licences and enter the Medical Register, it was still not mandatory for universities nor medical schools to train them. Thus, institutional and educational barriers to practice remained a common feature and women struggled to access the courses necessary for examination.

Concurrent to women’s struggles to gain entry, the Faculty were also facing challenges to their legitimacy and identity. In the decades following the 1858 Medical Act, the newly-created General Medical Council (GMC) was in the process of creating uniformed licensing and education systems to cover the entirety of the United Kingdom. If enacted, this Medical (Amendment) Act would remove the power of the individual medical corporations in favour of a single Scottish medical authority and a single Scottish licencing board – to be managed predominantly by the universities. In 1883, the Faculty petitioned the House of Lords against the proposed amendments, stating that:

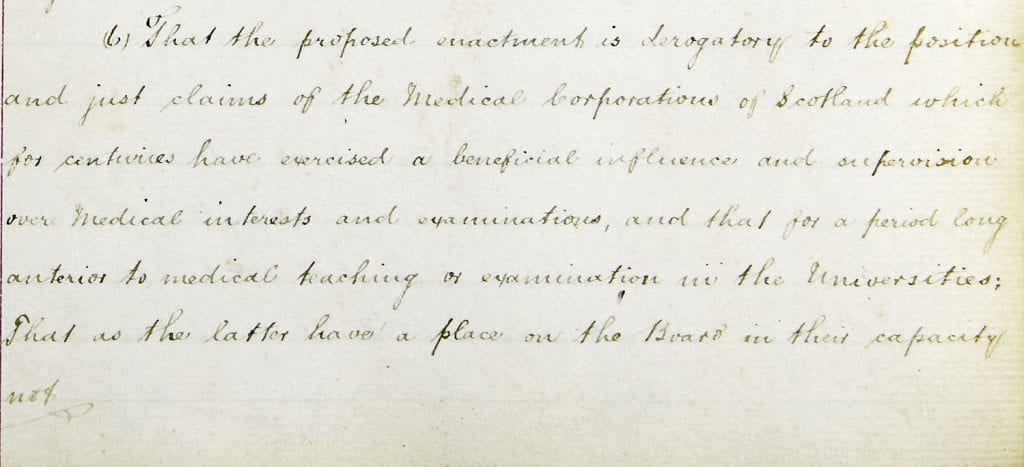

The Proposed enactment is derogatory to the position and just claims of the Medical Corporations of Scotland which for centuries have exercised a beneficial influence and supervision over medical interests…the body assigned to Scotland is less than that to which this division of the Kingdom is justly entitled.’ [1]

Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (April 1883)

Though not against standardising medical education and examination, the Faculty was equally aware of the imminent threat to their professional authority, as were the Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, who were similarly motivated to maintain their respective power and sovereignty.

Consequently, in the face of this growing pressure, the three medical authorities entered into negotiations to develop a ‘Conjoint’ scheme of examinations, later known as the Triple Qualification [2]. This pre-empted the proposals of the GMC by establishing a voluntary single licensing board in Scotland but at the same time ensured the autonomous survival of each medical body. The Conjoint Scheme created Diplomas in Medicine, Surgery and Midwifery to be offered in tandem by the Faculty in Glasgow and the Royal Colleges in Edinburgh, who agreed that:

‘While reserving to itself liberty to confer its Higher Qualification or Qualifications as it may deem proper…on and after the first day of October 1884 it shall abstain from the exercise of its power of granting Licences separately and…that the three Medical Authorities shall cooperate to form an Examining Board.

A Candidate on passing the Third Examination shall be admitted and receive Diplomas as – Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.’ [3]

‘A Scheme for Conjoint Examinations’ (March 1884)

Having previously fought fiercely to provide single licenses individually, this was a significant development in the relationship between the Faculty and the Royal Colleges, emphasising the greater threat posed by absorption by the GMC. Each body could still offer single Fellowship and other post-registration licenses. It is clear that their efforts were not in vain, as following the establishment of the Conjoint Examination the Faculty then petitioned the House of Commons arguing:

‘[The Bill] has no validity in Scotland, as by voluntary agreement…the three Corporations of Scotland have decided to conduct all their Examinations in combination…the number of portals to the profession in Scotland outside the Universities will be reduced to one.’ [4]

Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (July 1884)

Ultimately, through cooperation with the other medical bodies in Scotland, the Faculty protected their professional identity and autonomy while also preserving the elevated standard of medical education and limiting portals of entry to medical practice.

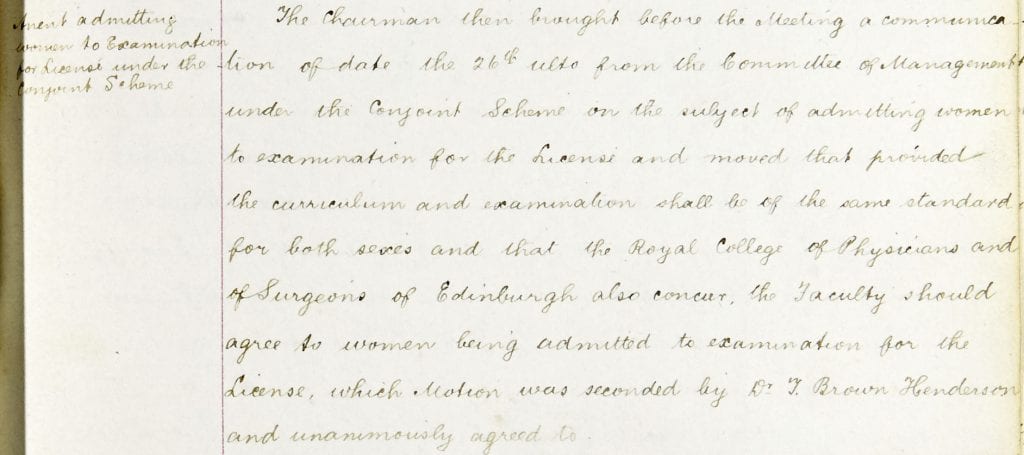

Moreover, the Triple Qualification also, albeit inadvertently, created a viable pathway for women to access medical qualifications. Due to the fact that the vast majority of students in the extramural schools followed the Triple Qualification curriculum, and that women were unable to study at the universities, the Conjoint examination became the primary means through which women could obtain their licences. In 1886, the Committee of Management for the Conjoint Scheme formally allowed women entry to the exam, six years before the universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow allowed women to enter their medical schools [5].

In 1886, the Faculty further included the rule as an amendment to their own Regulations:

‘Admission to the Licentiateship of the Faculty shall be open to women equally with men.’ [6]

‘Regulations of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow’ (April 1886)

What began as a scheme to preserve the authority of the Faculty thus became a crucial stepping stone towards gender equality in medicine in Scotland. Soon after, a number of women became Licentiates of the Faculty as well as the Royal Colleges and gained entry into the Medical Register. More information about these pioneering women can be found in our post by our Honorary Librarian, Dr Morven McElroy, here.

The impact of the Triple Qualification and the role of the Faculty in creating pathways to female medical education is an under-acknowledged yet significant part of not only the history of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, but also the history of women’s access to the medical profession in Britain.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

[1] RCPSG, GB 250 1/1/1/10 College Minutes, ‘Petition to House of Lords’ (17th April 1883), pp. 557-560

[2] RCPSG, GB 250 1/1/1/11, College Minutes, ‘Licence – scheme for Conjoint examinations’ (3rd March 1884), p. 12

[3] Ibid, p. 16

[4] RCPSG GB 250 1/1/1/11, College Minutes, ‘Petition against’ (7th July 1884) pp. 42-44

[5] RCPSG GB 250 1/1/1/11, College Minutes, ‘Anent admitting women to examination for Licence under the Conjoint Scheme’ (1st Feb 1886) p. 136

[6] RCPSG GB 250 1/1/1/11, College Minutes, ‘Regulations of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow’ (5th April 1886) pp. 152-153

Further Reading:

A. Hull and J. Geyer-Kordesch, The Shaping of the Medical Profession: The History of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, 1858-1999 (London: The Hambleon Press, 1999)

H.M. Dingwall, ‘The Triple Qualification examination of the Scottish medical and surgical colleges, 1884-1993’ Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 40 (2010) pp. 269-76

M. Rhodes, ‘Women in medicine: Doctors and Nurses, 1850-1920’ in D. Brunton (ed.) Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe, 1800-1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004)

J. N. Burstyn, ‘Education and Sex: The Medical Case against Higher Education for Women in England, 1870-1900’ Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117:2 (1973) pp. 79-89

Leave a Reply