Written by Laura Sutherland

Laura is a student at the University of Strathclyde studying for an MSc in Health History. She is currently undertaking a work placement with us to look at College “Firsts”. Her research focused particularly on our international members and fellows.

During my time at the Royal College, I have been delving further into its international history, with the hopes of uncovering the previously under researched stories of the first female international licentiates to pass the Scottish Triple Qualification (TQ) and practice medicine. The TQ was a qualification awarded jointly between the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and allowed those who gained it to practice medicine across the UK. The research into the vital international connections of the college has already begun through the work of Taweel Ali, Kristin Hay and Monique Lerpinière, and my hope was to contribute to this ever-growing research through my own.

Jane Louisa Jarrett Birkett

Through this research, I discovered Jane Louisa Jarrett Birkett who I believe, at 21 years old, was the first women born outside of the UK to pass the TQ here at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow in 1887.

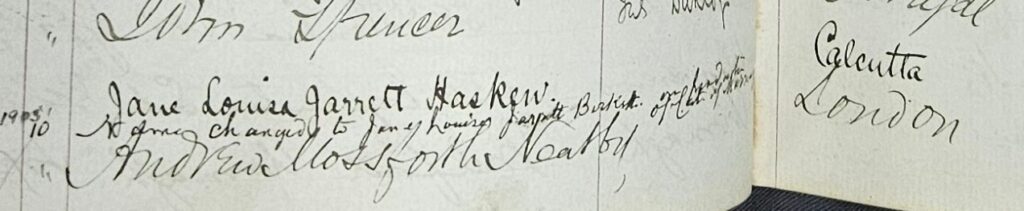

Jane Louisa Jarrett Birkett’s signature upon gaining the Triple Qualification

Birkett was born in 1865 in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), India to parents Edward Jarrett Haskew and Amelia Rebecca Jemima Haskew. She was the oldest of 11 children. She made the journey to the UK to study and studied medicine at the London School of Medicine for Women, before qualifying in Scotland. Birkett joined the UK Medical Register as soon as she qualified but went on to study for a further year in Brussels before returning to India to begin her professional career.

Upon returning to India, Birkett joined the Church Missionary Society (CMS) and worked for the Zenana Bible and Medical Missions. Through this, she gained the position as leading medical officer of the Lady Kinnaird Memorial Hospital in Lucknow. She was also placed in charge of Lucknow Medical Mission, which she led for many years. Whilst working here she met her husband Rev. Arthur Ismay Birkett, who was also a member of the CMS based in Lucknow, marrying him in 1899.

In 1900 Birkett became the first medical member of the CMS to begin working long-term in the Rajputana region and relocated here alongside her husband. Whilst working here she reported treating a variety of ailments, from tuberculosis to pneumonia, and from eye infections to cancer. She soon came to discover that the facilities to treat patients the way she would like did not exist and demanded that the CMS provide funds to create a small but serviceable hospital. This resulted in the building of a three-roomed dispensary and two separate buildings in 1905, with one acting as an inpatient facility for three men and the following building allowing for three female inpatients. The following year, 11,878 outpatients were treated within the new dispensary and 32 inpatients were admitted to the small hospital.

Birkett seemingly remained in this position until the death of Arthur in 1916, upon which she returned to England. This stay was short lived however, as she could not contain her drive for medical work, and she returned to India after only 3 years in England. She continued to work until her retirement in 1922.

Jane Louisa Jarrett Birkett is only one of many who paved the way for women’s rights within the medical profession but is undeniable that her contribution as one of the firsts is vital.

Annie Wardlaw Jagannadham

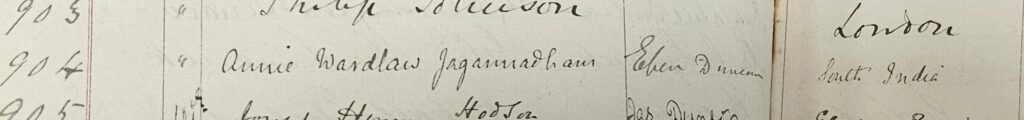

Another woman who paved the way through her involvement with the Royal College is Annie Wardlaw Jagannadham. Jagannadham made history in 1890 as not only one of the first women to pass the TQ but as the first Indian women to fully qualify to practice medicine in the UK and to be entered into the British Medical Register.

Jagannadham was born in 1864 in Visakhapatnam, India. She studied medicine initially in Madras, and after three years she moved on to study at the Edinburgh Medical School for Women and registered here in 1888. Whilst in Edinburgh she studied under the famous Sophia Jex-Blake (who was a member of the Edinburgh Seven) and became her first Indian student. As well as passing the TQ, Jagannadham also passed the Examination for the Certificate of Efficiency in Psychological Medicine, allowing her to broaden her medical scope and knowledge.

After graduation she remained in Edinburgh for a year, working as the house officer in Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children. In 1892 she returned to India and became the house surgeon in Cama Hospital in Mumbai, working under Edith Pechey-Phipson (another of the Edinburgh Seven)

Tragically, she died from tuberculosis at only 30 years of age.

Although Jagannadham’s life was cut short, there is no denying the significance of her actions as not only a female doctor but as a trailblazer for those looking to travel from overseas to study and qualify for medicine within the UK.

Annie Wardlaw Jagannadham’s signature

Kadambini Ganguly

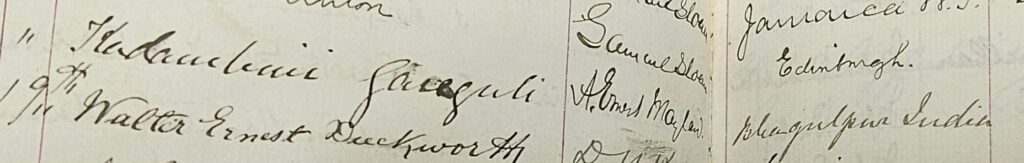

Another woman who cannot be missed in the discussion of female international licentiates is Kadambini Ganguly. Ganguly was born in 1861 in Bhagalpur, India and passed the TQ in 1893, just three years after Jagannadham first passed.

Ganguly had already been making history in India before her arrival in the UK. She had previously attended Bethune College (which was affiliated with the University of Calcutta) and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1883. This had made her the first women to graduate from university in India. The very same year she became the first women admitted to Calcutta Medical College. Incredibly, she had married just before this and was now balancing the study of medicine and the raising of eight children.

This seemingly did not phase her, and she was awarded the Graduate of Bengal Medical College degree in 1886. She began work as an assistant at the Lady Dufferin Hospital in Calcutta shortly afterwards, which focused on the provision of women’s healthcare.

However, this wasn’t enough for Ganguly, and she subsequently made the trip to Scotland where, as previously mentioned, she gained the TQ.

Kadambini Gangulys’s signature

Ganguly then returned to India where she resumed her role as a practicing physician. She gained popularity quickly and was often in high demand – she was sought after by, and treated, the Nepalese Royal family.

Ganguly was not only successful within the field of medicine but seemed determined to live life to the fullest. She was involved in various organisations, and in 1889 she became a delegate to the fifth session of the Indian National Congress and in 1906 she played a crucial role in the organisation of the Women’s Conference in Calcutta.

Ganguly worked until the very end, and died 3rd October 1923, having performed surgery earlier in the day.

There is no denying that the history of these women, and no doubt countless others just like them, is crucial not only in the development of the medical sphere worldwide, but also our understanding of the role that the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow has to play within this. These three women are vital puzzle pieces within all of this, and without their contributions and endless dedication to the field of medicine the world would no doubt be a very different shape.