As part of our Carnegie Trust-funded research project with Dr Cheryl McGeachan, A Distinctly Scottish Surgeon? Uncovering Police Surgery in 19th Century Scotland, we’ve been looking at the variety of cases police surgeons were involved in during this period. One particularly interesting case was part of a spate of reported cases of hydrophobia in Glasgow during the 1870s. Hydrophobia was the name given to rabies, when the disease was little understood, and carried with it a palpable sense of fear.

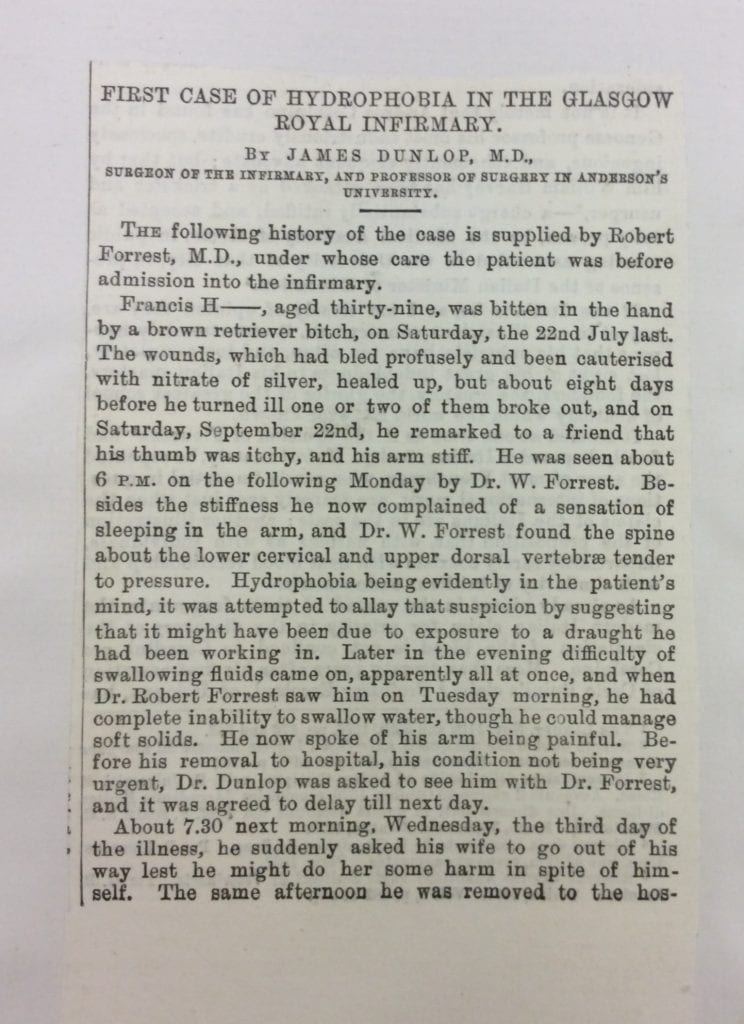

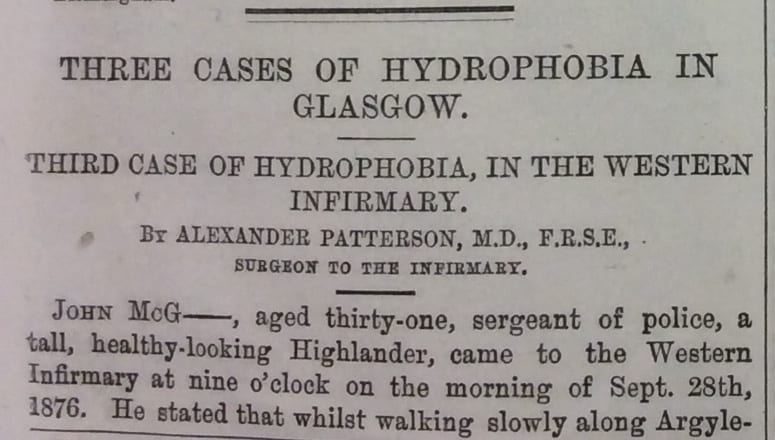

The case of hydrophobia encountered by the Glasgow police surgeon Dr Macgill in 1876 was reported in The Lancet, as the third of a series, published between January and February 1877. The first case (image below) and second case were treated in the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, while the third was treated at the Western Infirmary.

The patient in the third case was a police sergeant, John McG_, “a tall, healthy-looking Highlander”. He was seen by the house surgeon at the Western Infirmary on 28th September 1876, after receiving a bite from a dog “whilst walking slowly along Argyll Street at half past four in the morning” on duty, it is assumed. At the Western “the wounds were washed with the strongest watery solution of carbolic acid, and gauze dressing applied.” In this first visit to the hospital immediately after the bite, and a month before any symptoms, he told the house surgeon “that he dreaded taking hydrophobia”.

A month later he was brought to the Western with “supposed symptoms of hydrophobia”. The previous day he had sent for Dr Macgill, the police surgeon, who saw him at home after he had complained of some early symptoms – pain spreading around the wound, vomiting, and inability to swallow. Dr Macgill then “recommended him to the hospital”.

A marked feature of the description of the case and of the patient, is the presence of fear, dread and fright. As mentioned above, directly after receiving the bite the patient told the hospital house surgeon “that he dreaded taking hydrophobia”. The surgeon tried to reassure him “that no such result was to be feared”.When he was re-admitted a month later and observed by the report’s author Dr Patterson, “he had a worn, dejected and frightened look in his face”. When the patient himself described his symptoms on the days leading up to his admittance, he describes how he “awoke in ‘a great fright’, and slept badly the remainder of the night”.

The symptoms mentioned above are described as worsening during the short period of admittance to the Infirmary. On the presentation of water to drink, the patient was “seized by spasm” so severe that “he seemed on the point of suffocation”. The day after being admitted he “requested his minister to be sent for” “and on first seeing him he was seized with a severe spasm”, before being able to speak to him “calmly of his approaching death”. Later that day after trying to take some milk and having another severe spasm, when it subsided, instead of the usual low sigh, he made “a peculiar, prolonged sound, which resembled nothing so much as the baying of a dog as heard at a distance on a calm summer night in the country”.

During and after these episodes, the patient was being treated with “a hypodermic injection of morphia every four hours” and was to have “powdered sugar and starch placed on his tongue”. As he became more restless he was “ordered to be placed under the influence of chloroform”. Also, “eight ounces of beef tea and some port wine to be thrown into his stomach by the tube”.

In moments of calm the patient requested that the house surgeon write to his wife, and “he himself wrote his name in the journal with a steady hand”. He also received a visit from the police surgeon, and reported that “in the event of his recovering he was to have a month’s leave”.

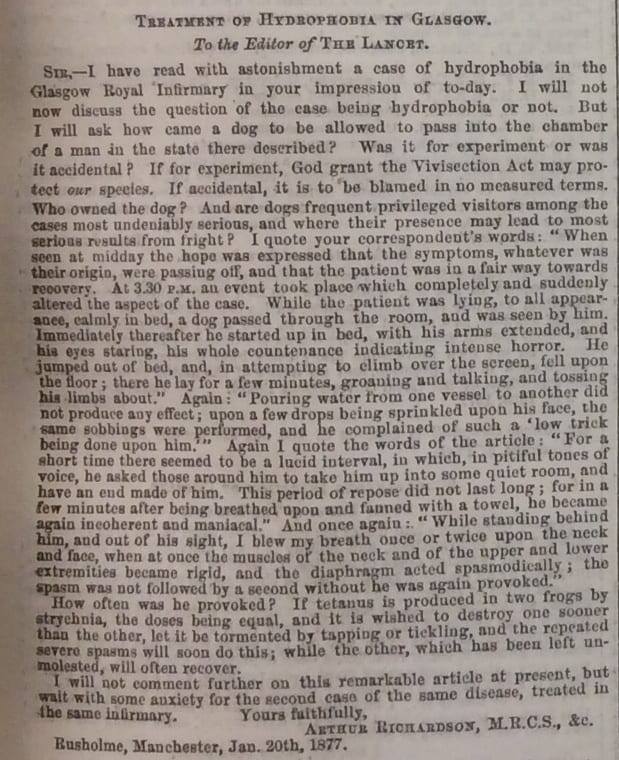

That night he became “wildly delirious” again however. He “asks to be tied, lest he should harm anyone near him”. Dr Patterson states that this is not required. At this time the patient “says he should not have been ill had he not read of the second case at the Royal Infirmary”. This suggest that this case was reported in the local press, as well as in the Lancet (as the Lancet article wasn’t published until after his death). It also highlights an intriguing connection between the reporting of disease, of public fear, and medical treatment at this time. Letters to the medical press responding to the reporting of the cases shows the kind of professional debate and uncertainty about the disease and its treatment (for example, the letter below from January 27th, 1877).

The next day, 1st November, the patient “fell asleep at 4 [am], and slept until 7, at which he had a long epileptiform fit. At 8.30 he became gradually semi-comatose, his skin being covered with a clammy perspiration, until 10am, when he died”. A post-mortem took place the next day – “every organ in the body was healthy. The brain and its membranes were slightly congested, which may have been the effect, rather than the cause, of the disease”. The report of the third case is appended by a Pathological Report by Dr Joseph Coats, which highlights the attempts being made in the city to understand this disease. A vaccine to treat rabies was introduced in 1885, by Louis Pasteur. This has developed over the years but rabies persists as a serious health issue in many countries. On 28th September each year, Pasteur’s birthday, World Rabies Day marks an on-going global campaign to raise awareness of rabies prevention.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.