In this post by our Digitisation Project Intern, we look at our amputation instruments, while referring to the work of Maister Peter Lowe, College founder and 16th century surgeon.

The surgical procedure of an amputation involves the removal of a section of a limb of the body. The volume of tissue removed from the body depends on a variety of factors, including the severity of the patient’s condition.

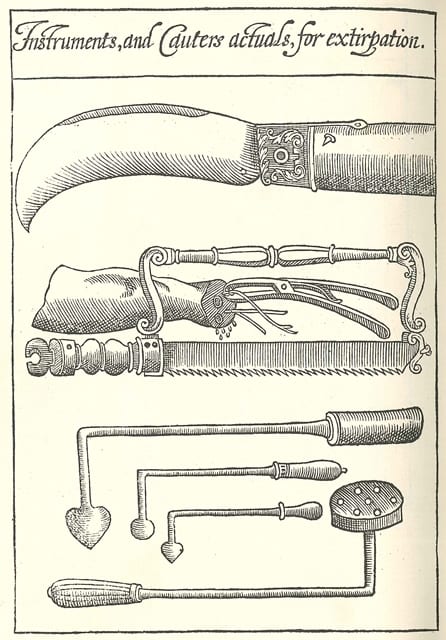

Woodcut illustration, 2nd ed. of Lowe’s Chirurgerie (1612)

It is uncertain as to how long amputations have been a regular form of surgical treatment, however the term can be traced back to the 16th century. For example, Peter Lowe uses the term “amputation” when describing how to treat a gangrenous limb in his 1597 work The Whole Course of Chirurgerie [1]. Here he explains how the operation should be carried out, referencing the works of previous scholars:

“The judgements are, that it is for the most part incurable, and the patient will die in a cold sweat. The cure, in so much as may be, consists only in amputation of the member, which shall be done in this manner, for the patient must first be told of the danger, because often death ensues, as you have heard, either from apprehension, weakness, or loss of blood.”

It has only been within the last 170 years that amputations, and surgical procedures in general, have been performed in a safe manner, e.g. with the patient under anaesthesia. Prior to this, the limb was removed as quickly as possible. A successful and speedy amputation required precision, strength, skill, and a steady hand, as well as a set of sharp amputation instruments!

Mid 19th century amputation set

Within the museum collection are examples of amputation sets from the 1800-1900s.

Several components make up a set, from trephine heads to amputation saws to tourniquets. Each instrument would be used at a different stage of the surgical procedure. Let’s take a look at how a lower limb amputation would be performed.

First of all, the patient would be prepped for the surgery. In the days before pain relief, alcohol was the method used to calm the nerves. The patient would be given some rum or whisky, and then wheeled into the surgical theatre. Most likely the theatre would be structured with the operating table in the centre of the room surrounded by rows and rows of stands for spectators. Spectators would include the students of the chief surgeon involved in the procedure- not only was this a surgical operation, it was also a lesson. Once the patient was placed on the operating table, the chief surgeon would enter the theatre and the operation would commence.

One of the major dangers of amputating a limb is blood loss. Several blood vessels must be carefully salvaged during the procedure in order to limit haemorrhaging [1]. To enable the surgeon to operate on a bloodless area of the body, a Tourniquet was applied proximal to the site of amputation (a couple of inches above the site of incision).

“The use of the ribband is diverse. First it holds the member hard, that the instrument may curve more surely. Secondly, that the feeling of the whole part is stupefied and rendered insensible. Thirdly, the flow of blood is stopped by it. Fourthly, it holds up the skin and muscles, which cover the bone after it is loosed, and so makes it easier to heal.”[1]

Example of a tourniquet from an amputation set

The tourniquet would have been tightened in order to restrict blood flow and reduce haemorrhaging. It would also have reduced sensation to the limb, providing slight pain relief. However, this would also mean that oxygen was restricted. Hence another reason as to why amputations were performed as quickly as possible.

The initial incision would have been made with a sharp amputation knife. Amputation knives evolved in shape over the years, from a curved blade to a straight blade. Peter Lowe comments on the use of a curved blade for the procedure:

“…we cut the flesh with a razor or knife, that is somewhat crooked like a hook…”[1]

The blade was curved in order to easily cut in a circular manner around the bone (see image from Lowe’s book above) [2]. Amputation blades became straighter as the incision technique evolved. An example of a straight amputation knife is that of the Liston Knife. With a straight and sharp blade, this knife was named after the Scottish surgeon Robert Liston. Liston is best known for being the first surgeon in Europe to perform an amputation procedure with the patient under anaesthesia [3].

Liston knife, mid 19th century

The straight blades enabled the surgeon to dissect more precisely in order to form the flap of skin and muscle that would become the new limb stump.

As one can imagine, bone tissue would not be easily removed by an amputation knife. Instead, an amputation saw was required to separate bone. Amputation saws were similar to those found in carpentry, with sharp teeth to dig into and tear bone tissue for a quick procedure.

Amputation saw, mid 19th century

Aside from the major dissecting tools, there are more specialised instruments within an amputation set that we must consider. One of the main risks of an amputation operation was death by haemorrhaging. For years, the letting of blood was used to treat certain ailments according to the ancient teaching of the “Four Humors”. However, in a surgical procedure the major loss of blood was something to be avoided. In order to prevent the haemorrhaging of dissected vessels, the surgeon would have used a Ligature to tie off the vessel and disrupt blood flow. This technique was pioneered by French surgeon Ambroise Paré during the 1500s [4].

Found within our amputation sets are trephine heads with accompanying handles. Rather than being used during an amputation procedure, trephine heads were used to drill into the skull to treat conditions by relieving intracranial pressure. Nowadays, access to the brain via the skull is achieved with the use of electric drills.

Trephine, mid 19th century

Amputation procedures have changed dramatically since the days before anaesthesia and antiseptics, but the risks have remained. Blood loss, sepsis, and infection are factors that can still occur today. Thankfully, their likelihood is much lower than they were 170 years ago.

References

- Lowe, P., 1597. The Whole Course of Chirurgerie.

- Science Museum, 2016. Amputation Knife, Germany, 1701-1800. Brought to Life: Exploring the History of Medicine. [online] Available at: http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display?id=5510

- Liston, R., 1847. To the Editor. The Lancet, 1, p. 8.

- Hernigou, P., 2013. Ambroise Paré II: Paré’s contribution to amputation and ligature. International Orthopaedics, 37(4), pp. 769-772.

I would love to visit and see some of these exhibits for myself and read Lowe’s book. Has it been digitalised? Thanks, Margaret