Thursday 18th June marks the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, where 100,000 allied troops led by the Duke of Wellington faced off against 125,000 French troops under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte. This epic battle, one of the most important European events of the 19th century, continues to fascinate historians and the public alike. The bicentenary is being marked across the continent with a range of commemorations, re-enactments and other events examining themes such as military strategy, politics and power struggles, and the bravery of individual soldiers on both sides. Our latest monthly exhibition focuses on the impact of medicine and surgery on the battlefield at Waterloo. For opening times, please visit our website.

Waterloo can be viewed as a proving ground for some of the medical and surgical advancements made during the course of the Napoleonic wars. The College Library and Archive has a range of resources for anyone looking to find out more about the roles of medics and surgeons at Waterloo.

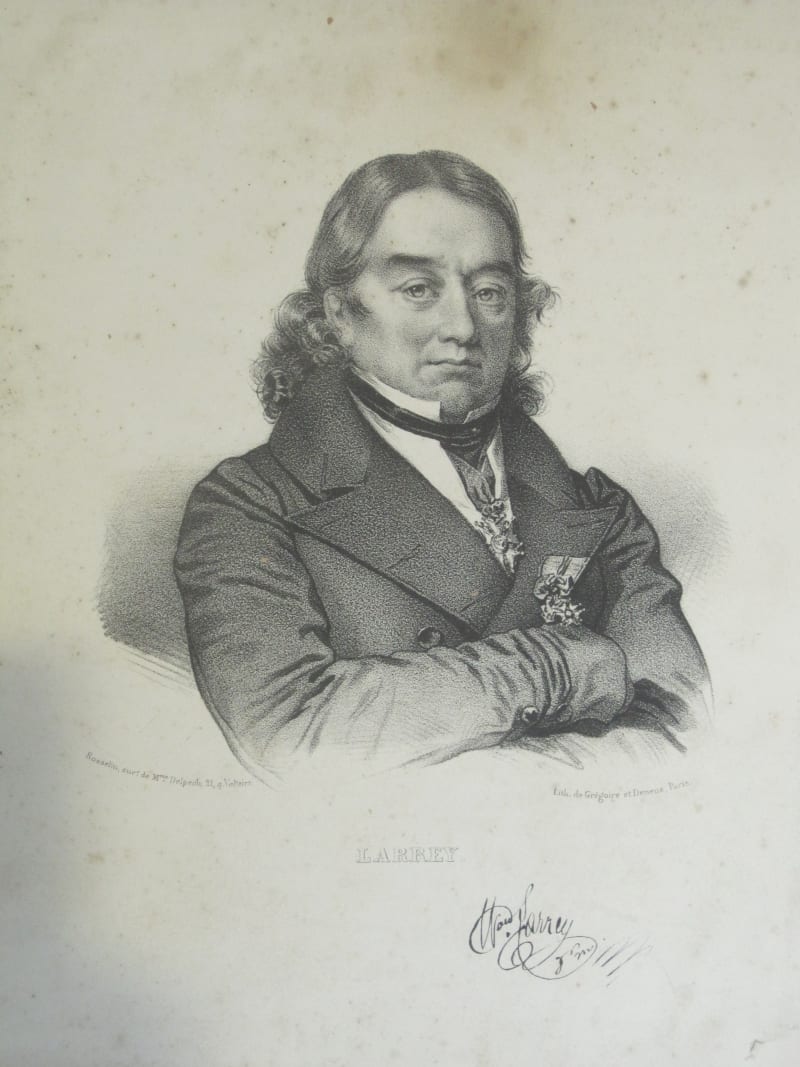

Larrey and the Field Ambulance

In order for battlefield injuries to be treated by army surgeons during the Napoleonic wars, the wounded men first had to be moved to a place of relative safety. The difficulty of this could vary wildly depending on terrain, weather, and the type of transport available. Different types of carts and wagons were variously used to transport injured soldiers, often with several men sharing the vehicle at the same time, no doubt exacerbating their injuries. This method of evacuation was slow, cumbersome, and could be extremely painful for the wounded men. Those who could not be safely transported would likely die on the battlefield.

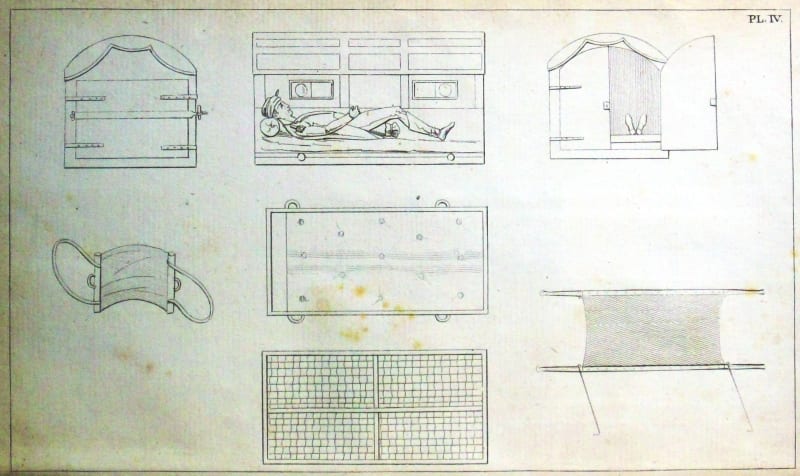

The French Army, however, had a solution of sorts, provided by the experienced military surgeon, Jean Dominique Larrey. Larrey devised the idea of the ‘flying ambulance’, a support service which used specially designed vehicles to move wounded soldiers away from the battlefield as quickly and painlessly as possible. This two-wheeled wagon provided cover as well as padding on the inside. The rear doors opened to allow stretchers to slide in and out.

© Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images / CC BY 4.0

http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0058526.html

This early example of an ambulance provided a terrific boost to the French army, meaning they were able to bring medical aid to their wounded troops much faster than surgeons on the Allied side. This innovation also helped to secure Larrey’s reputation, and he was made Chirurgien en Chef de la Grande Armée by Napoleon in 1812.

Plate from Larrey’s “Mémoires de Chirurgie Militaire” Paris, 1812, showing the interior of the ambulance

Sir Charles Bell

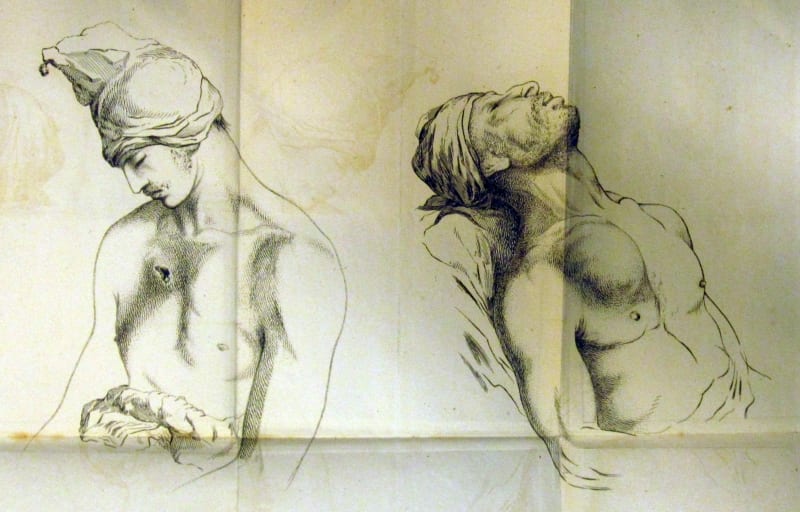

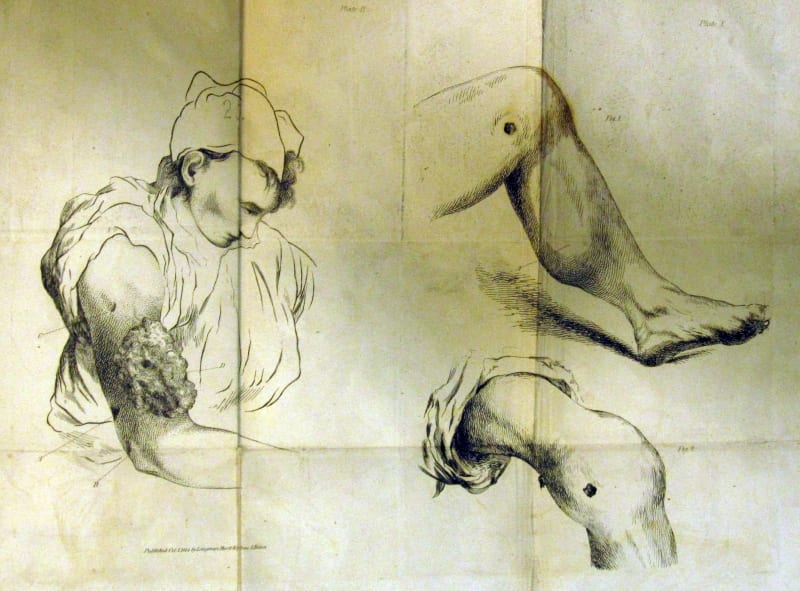

Bell was a surgeon and anatomist, who acquired a sound knowledge of gunshot wounds while volunteering as a surgeon during the Peninsular War. He offered his services again after the Battle of Waterloo, arriving in Brussels with his surgical instruments 10 days after the battle to help tend to the thousands of wounded men. He worked ceaselessly, often operating for up to 12 hours a day until

“my clothes [were] stiff with blood and my arms powerless with the exertion of using my knife.”

Bell was also a very talented artist, and made detailed sketches of many of the cases he treated, later making them into a series of watercolours. A selection of these can be found on the Wellcome Images website. Below are two plates from the College’s copy of Bell’s Dissertation on Gun-Shot Wounds (1814).

Sir James McGrigor, Wellington’s Surgeon-General

McGrigor, a Scottish physician, is credited with working to improve the conditions of military medical care for the Allies throughout the Peninsular War (1807-1814). The improvements made in surgical techniques and the management of field hospitals in this conflict were subsequently carried into the Battle of Waterloo. This time, however, the number of skilled surgeons on the ground was lacking, and many battalions even lacked stretcher-bearers and basic medical and surgical supplies.

The armistice of 1814, the year before Waterloo, meant that McGrigor was able to visit a number of military hospitals in France, and even meet with Larrey and some of his colleagues. He no doubt had great admiration for the system of removal devised by Larrey, and was dismayed by Wellington’s refusal to incorporate the ambulance into his own army.

“I once proposed our adoption of it in Spain to Lord Wellington; but he would not hear of it; nor would he give the credit of humanity to Napoleon, as the motive for his introduction of it into the army.”

This contrast with the French army is perhaps surprising. One would naturally assume that the victorious side in this battle would have had superior medical and surgical provision. Waterloo was undoubtedly a great military victory for Wellington, but it is questionable whether it should be viewed as a medical success.

McGrigor’s most enduring work was carried out both before and after the Battle of Waterloo, as he improved army medicine and surgery during the Peninsular War, and carried out a great deal of reform work as Director-General of the Army Medical Service between 1815 and 1851. He introduced the use of the stethoscope and the tourniquet to military medicine and encouraged speed, efficiency and sharp, clean instruments in surgery. These changes, as well as many others he instigated during his time as Director-General, had a firm and lasting impact on the standard of military medicine in the British Army. He is perhaps best known today as the man responsible for laying the foundations of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Resources in the College Library

If you would like to learn more about the impact of medicine and surgery at Waterloo, the College Library holds a good selection of interesting books on this subject:

Arnott, J.M., 1843. The Hunterian Oration, delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons, in London, on the fourteenth of February, 1843 [with an obituary of J.D. Larrey]. London: John Scott. – Pamphlets : William Mackenzie Collection, vol. 42

Bell, C., 1814. A Dissertation on Gun-Shot Wounds. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. – Murray Bookcase: BEL

Blanco, R.L., 1974. Wellington’s surgeon general, Sir James McGrigor. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press. – Reading Room: WZ 100 MCG

Crumplin, M.K.H. and Starling, P.H., 2005. A surgical artist at war: the paintings and sketches of Sir Charles Bell. Edinburgh: Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. – Reading Room: WZ 330 CRU

Gore, A.A., 1872. Brief historical memoir of the Army Medical Service, 1346-1871. Sandgate: R. Stace. – Pamphlets : Medical, vol. 51

Howard, M., 2002. Wellington’s doctors: the British Army medical services in the Napoleonic Wars. Staplehurst, Kent: Spellmount. – Reading Room: WZ 60 HOW

Larrey, J.D., 1812. Mémoires de chirurgie militaire, et campagnes de D. J. Larrey. Paris: J. Smith. – Bookstore: LAR

Lincoln, M. and National Maritime Museum (Great Britain) eds., 2005. Nelson & Napoléon. London: National Maritime Museum. – Reading Room: DA 87.1.N4 LIN

Miles, A.E.W., 2009. The accidental birth of military medicine: the origins of the Royal Army Medical Corps. London: Civic Books. – Reading Room: UH 215 FA1

Thomson, J., 1816. Report of observations made in the British military hospitals in Belgium, after the battle of Waterloo; with some remarks upon amputation. Edinburgh: Blackwood. – Bookstore: THO

[…] Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow: Medicine and Surgery at the Battle of Waterloo […]

[…] Medicine and Surgery at the Battle of Waterloo […]

[…] Medicine and Surgery at the Battle of Waterloo […]

I would just like to mention the book I wrote (published may 2015) on sir Charles Bell and the days he spent at Brussels after Waterloo.

Hope you will like it : Charles Bell, Chirurgien à Waterloo, ed Michalon, Paris , 2015.

Thanks for your comments,

Martine devillers-Argouarc’h

[…] day after: chirurgie op het slagveld van […]