Welcome to our first post of 2015, and a happy new year to all of our readers! This month we have installed a new temporary exhibition in Crush Hall, on the history of diabetes. Visitors are welcome to visit the College to view the exhibition on Monday afternoons between 2pm and 5pm, or at other times by appointment.

Early Writings

The history of diabetes begins around 1550 BC, with the Papyrus Ebers. This Ancient Egyptian papyrus, named for the German Egyptologist Georg Ebers, contains what is believed to be the first written reference to diabetes mellitus, and provides remedies for the treatment of polyuria.

A measuring glass filled with Water from the Bird pond, Elderberry, Fibres of the asit plant, Fresh Milk, Beer-Swill, Flower of the Cucumber, and Green Dates[1]

There is fairly widespread agreement that the papyrus does indeed refer to diabetes, but overall the archaic phraseology of the document makes it extremely difficult for translators to properly identify the names of diseases and drugs.

The earliest reasonably accurate account of diabetes comes from Aretaeus the Cappadocian (81-138 AD). Aretaeus is also responsible for giving the disease its present name. He coined the name using the Greek word, διαβήτης, meaning “siphon” (from διαβαίνειν, meaning “to pass through”), after noting the symptomatic thirst and frequent urination displayed by patients.

Diabetes is a wonderful affection, not very frequent among men, being a melting down of the flesh and limbs into urine. Its cause is of a cold and humid nature, as in dropsy. The course is the common one, namely, the kidneys and bladder; for the patients never stop making water, but the flow is incessant, as if from the opening of aqueducts.[2]

In the Middle Ages, the Persian polymath Avicenna (980-1037) gave an account of diabetes mellitus in his Canon of Medicine. He described a number of clinical features relating to diabetes, most notably the sweetness of the urine produced by diabetic patients.

Title page of Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine, Venice, 1544

During the Renaissance, the Swiss physician Paracelsus (1493-1541) observed a white residue that remained after he allowed the urine of diabetic patients to evaporate. However, he incorrectly identified this residue as salt, and decided that the great thirst displayed by diabetics was caused by deposits of salt in the kidneys.

“Wonderfully sweet”

Our present day understanding of diabetes starts to take a more familiar shape in the 17th century, thanks to the work of Thomas Willis (1621-1675). He noted, adding to the observations of Avicenna before him, the sweetness of urine in diabetes “as if imbued with sugar or honey”, and added the word “mellitus”. Willis was then able to differentiate between diabetes mellitus and the much rarer condition, diabetes insipidus.

Despite these advances, Willis did not understand what was actually causing this sweetness in the urine. He wrote, “why it should be so wonderfully sweet, like sugar or honey, is a knot not easie to untie.” Proof of the role of sugar in this phenomenon eventually arrived in 1776, courtesy of Matthew Dobson (1731-1784). In a paper published in Medical Observations and Inquiries, he proved through experiments carried out on the urine of a diabetic patient, that the ‘white cake’ was in fact sugar.

The Pancreas and the Discovery of Insulin

The role of the pancreas in diabetes was first suggested by Thomas Cawley in 1788, when he suggested in a case report that the disease may occur following injury to that particular organ. The definitive discovery of this role did not come until 1889, when Joseph von Meering and Oskar Minkowski carried out experiments on dogs as part of a study at the University of Strasbourg. The two men discovered that they were able to induce diabetes by removing the pancreas, and concluded that the pancreas was responsible for regulating blood sugar.

This discovery was furthered in 1910 by the work of the English physiologist, Sir Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer. Sir Edward suggested that the pancreas was responsible for producing a particular chemical and that diabetic patients were deficient in this chemical, which he proposed calling insulin. In 1921 two Canadian scientists, Frederick Banting and Charles Best, repeated the experiments of Meering and Minkowski and were successful in reversing the effects of the induced diabetes by injecting the dogs with purified insulin extracted from the pancreas. Although various dietary regimes and remedies for diabetes had been prescribed up to this point, with varying degrees of success, this was the first major breakthrough in establishing a treatment for the disease.

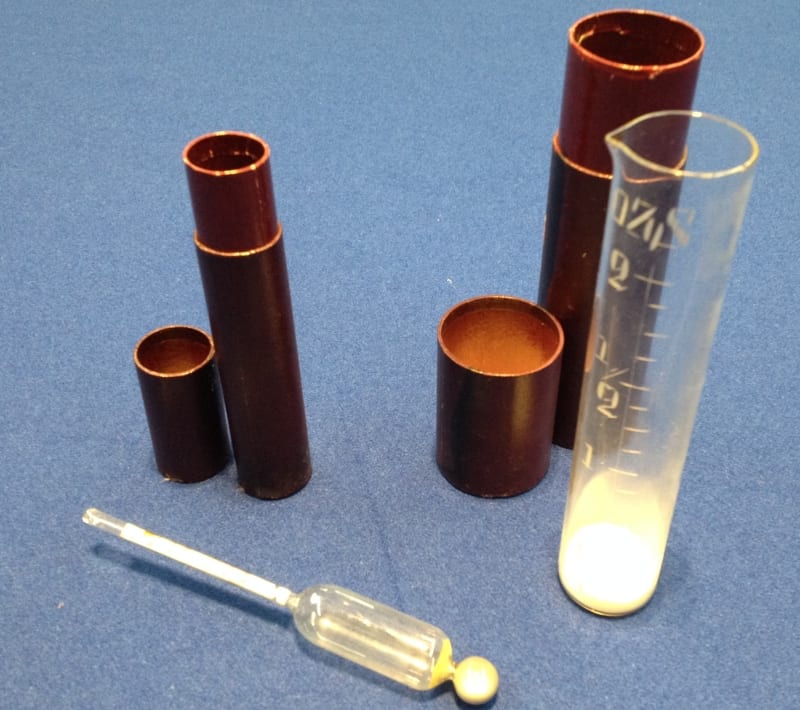

A urinometer and measuring cylinder. Used to test the specific gravity of urine, this device is helpful in assessing the amount of sugar present in a urine sample.

Type 1 & Type 2 Diabetes

The distinction between the two types of diabetes was first made around 400-500 AD by two Indian physicians, Sushruta and Charaka. They noted that one form of the disease affected children, while another was associated with adult obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. This distinction has been observed throughout the history of diabetes, but it was not clearly understood until the 20th century. In 1936, the English scientist Sir Harold Himsworth published a paper in the Lancet, proposing the idea that some diabetes patients have insulin resistance rather than insulin deficiency. This insulin resistance is now known to be a feature of the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, whereas insulin deficiency is associated with type 1.

The Diabetic Foot

As diabetes becomes increasingly prevalent in the 21st century, we are learning more about the wide range of complications the disease can potentially present. Among the most important of these is the diabetic foot. Diabetes can reduce the bloody supply to the foot, meaning diabetic patients are at a high risk of developing infections, arterial disease, and ulcers. For centuries the only available treatment was amputation, with many patients then going on to suffer severe blood loss and/or infection. Nowadays, amputation can usually be avoided thanks to preventative work carried out by medical professionals, as well as educating diabetic patients in how best to deal with their condition. The treatment of diabetic foot is studied in considerable detail by practitioners of podiatric medicine and practitioners in similar fields. However, the work required to prevent these complications is by no means limited to lower-limb specialists.

Conclusion

We can see several examples of diabetes being described and discussed in ancient medical writing. Nonetheless the disease was, for a long time, apparently very rare. Galen, for example, was certainly aware of the disease, but commented that he had only seen two cases in his career. This is in stark contrast to the global epidemic of diabetes we are witnessing now, as the disease has become one of the major public health crises of the 21st century. Although the epidemiology of diabetes is still vigorously debated, the dramatic increase in cases of type 2 diabetes is undoubtedly linked to increased rates of obesity. Our scientific understanding of diabetes has improved dramatically in the last century, but there is still much that we have to understand about the disease and how best to prevent it developing. This is made more challenging by the sheer scale of the problem, and the difficulties in organising a concerted, global effort to tackle the epidemic.

[1] Sanders, LJ (2002). From Thebes to Toronto and the 21st Century: An Incredible Journey. Diabetes Spectrum. Vol. 15(1).

[2] Aretaeus, of Cappadocia (1856) The extant works of Aretaeus, the Cappadocian, edited and translated by Francis Adams. Sydenham Society.

Reblogged this on Dr. Sriram Seshadri.