One of the archive volumes that we have digitised and made available on the College website (and at the bottom of this post) is a volume relating to a tour of George Buchanan in Prussia, Saxony, Austria, Styria, the Tyrol, Switzerland, the German States, Holland, Belgium and France in 1850.

Buchanan, then aged 23 and recently qualified in medicine, left Glasgow by train to Edinburgh on the 20th July and arrived home on the 19th October 1850. He was away for thirteen weeks and spent in all £60. Buchanan’s 1850 tour seems to have served two purposes. One was purely sightseeing, the other to further his professional education. In doing so he was not only following the example of many of his peers but also that of his father (Moses Buchanan, Professor of Anatomy at Anderson’s University, Glasgow) who had similarly travelled in Europe as a young man. In Aalster Hospital, Hamburg, when Buchanan inscribed his name in the visitor’s book, he found his father’s name a few pages back.

Buchanan’s journal is accompanied by line drawings, sketches and water colours as well as printed pictures acquired from newspapers and other sources during the course of his travels. He seems to have been particularly interested in regional costumes. In Hamburg he observed the servant girls who carried a “small basket shaped like a coffin and conceal it by throwing over a handsome shawl” and the flower girls who wore a “curious flat straw bonnet to support a basket of nosegays” (page 6). At Salzburg he describes the costume of the people as “very curious especially the head-dress which is a little covering of cloth of gold or silver shaped like a helmet and only on the back of the head” (page 108).

Costume at Hamburg

Buchanan’s trusty guide throughout his journey was his copy of Murray’s guide to the continent (Murray being the equivalent of the later Baedeker guide which supplanted Murray in popularity in the later 19th/early 20th century or today’s Lonely Planet or Rough Guides). The use of Murray signalled out the British traveller. On climbing up to view the river Elbe Buchanan writes that “I saw a lady and gentleman under a shed and knew them to be English by the way they were studying Murray” (page 51).

Buchanan’s drawing of the Elbe.

A drink after dinner and a comforting cigar were part of Buchanan’s existence. But, although a cigar smoker himself he was, on occasion surprised at the amount of smoking on the Continent. He writes: “At half past seven left for Berlin – got into a railway carriage second class. Seven gentlemen smoking cigars. A pretty thick atmosphere it made for that time in the morning – I knew if I was to make myself comfortable I must do as my neighbours so, after one or two gasps and a moderate sneezing I put on my cap lighted a cigar and began to puff like the best of them.” At Leipsig he saw a number of medical students waiting for a lecture “the majority with cigars lit” (page 36).

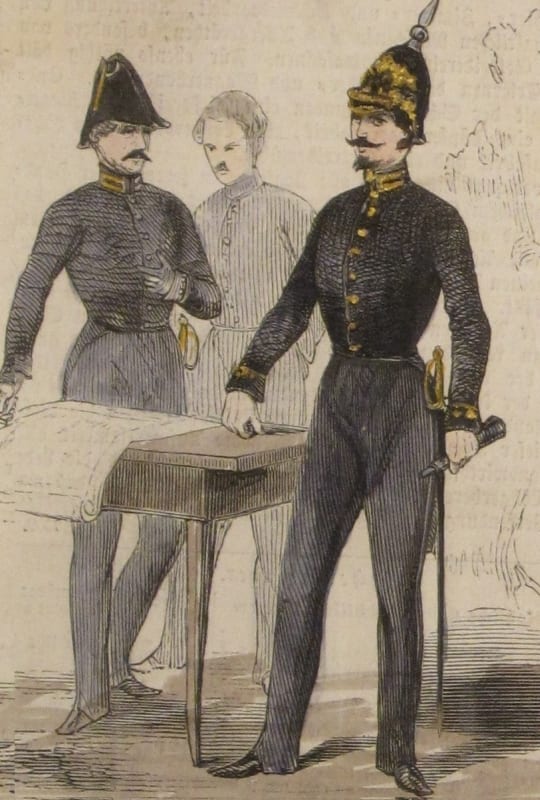

In 1848 revolution had spread throughout Europe and signs of the recent unrest were apparent in several places that Buchanan visited. Buchanan mentions that in the German states the army was ever present and that there was strict control on visitors: “the police at Berlin seem to have a thorough supervision of all that goes on for every stranger is reported as he arrives and by Police order my bill of the day’s expenses was presented to me every evening at the hotel.” The area around Hamburg was embroiled in war with Denmark, but the only mention Buchanan makes is of the wounded being taken to a hospital at Altona, a town quite close to Hamburg. At Dresden Buchanan visited the Royal apartments where he saw marks of bullets in the Queen’s sitting room and in another the handle of a jar on the mantelpiece was chipped off. At Vienna (page 73) Buchanan visited the university only to find it being used as an army barracks with the medical classes being taught in the hospital instead. At Munich, Buchanan had the opportunity of seeing a man being examined for a medical degree “the tribunal was somewhat more formidable in appearance than our ‘boards’. Six old gentlemen in capacious velvet cloaks and curious square topped velvet caps comprised the examining board. A handsome young man most elegantly dressed with a gilt hilted rapier by his side had read his thesis and was ‘maintaining’ it against an old boy who, from what I could gather, seemed to be putting leading questions on the subject of pneumonia”.

Student defending at thesis from Buchanan’s journal.

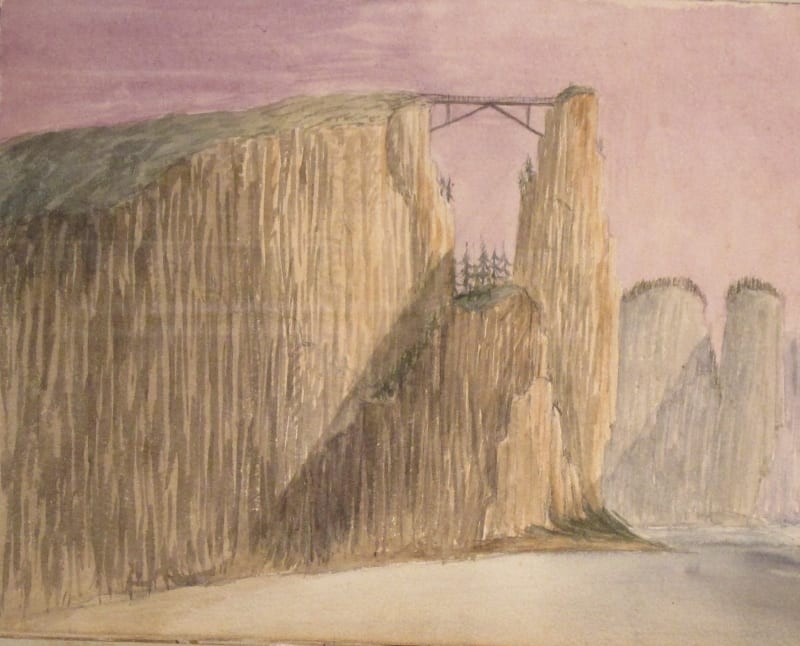

In addition to hospitals, Buchanan also visited spas and resorts. He describes the Baths of Pfeffers in some detail (page 193) being sandwiched in between precipices 600 feet in height with the light nearly shut out, the baths consisting of “two square buildings, damp dark uncomfortable places with about 300 apartments – more like a prison or dungeon than a bath house.” A path had been constructed along the face of the rock to see the source “the whole place is quite filled with a stifling steam which ascends from the hot sprint at the upper end . . . the most fearfully wild spot I ever was in”.

Buchanan’s drawing of the waters at Pfeffers.

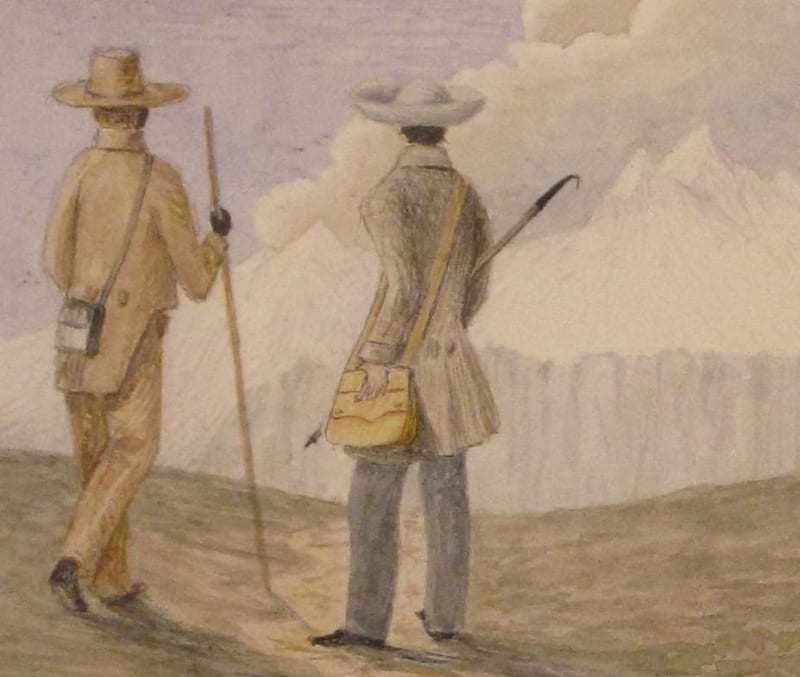

One of the great highlights of his trip was a walking tour through the Tyrol with a Swiss guide, Nicholas Andlegg who had acted as a guide to his uncle and cousin and sister previously. Buchanan describes Andlegg as a “sober, honest and obliging” man wearing a simple characteristic costume of “a short tailed coat of brown coarse woollen stuff trowsers and waistcoat of the same. A low crowned broad brimmed wide awake hat and a parchment covered knapsack completed his wardrobe.”

Buchanan and his mountain guide, Andregg.

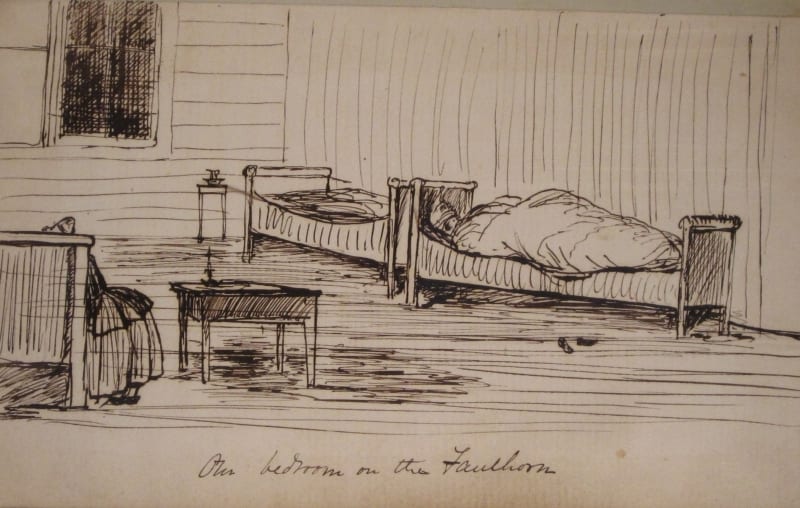

Buchanan describes in detail one particularly memorable event (page 232). Following what appears to have been a riotous evening of laughter and song with about 30 other travellers, 8,000 feet up at the Faulhorn Inn, Buchanan retired to his bed – the “most extraordinary specimen of furniture” he had ever slept in. He describes the bed as a “low box filled to the brim with straw, a carpet on the top of this and a sheet above all”. The pillow was an “elevated bundle of straw”. His covering was a “huge feather bed slightly damp and intensely cold” and heavy.

Buchanan’s bedroom at the Faulhorn Inn

He had just fallen to sleep when he was wakened by:

“a most extraordinary appearance – at the side of the bed, opposite me, was a person of the other sex engaged in making down the bed, and as the candle was set on the table, apparently she was going to pass the night in the same room. Mr Pickwick and the lady with yellow curl papers immediately occurred to me, only this lady was evidently a female domestic, and the scene was changed inasmuch as I was already in bed and nailed by the top covering, and the beds had no curtains. The tactics of that gentleman immediately suggested themselves to me, and as I was not very fluent at German I gave a hem! To shew I was there, and kept on my night cap in order that the lady, if she retained her reasoning powers, might judge from its conformation, that I was a male. Judge of my surprise when she looked round she only laughed and proceeded with her occupation. Time was precious – I must put a stop to the farce – I was about to argue the impropriety of the step and had just prepared a German sentence to open the conference, when to my relief she succeeded after great exertion in rolling into a bundle, top covering, carpet sheet and all, thereby shewing me that she was only employed in removing a bed from the room.”

He managed to persuade the woman to leave the bed as it was ready for when his friends came up who, of course, laughed heartily when they heard his story.

Buchanan was later to serve as a civilian surgeon during the Crimean War. His Crimean diaries have also been digitised and are available on the College website.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.