Written by Dr Theeba Krishnamoorthy

Theeba is a London-based physician who has spent the past few years uncovering the hidden stories of the first South Asian women doctors of the British Empire, writing them into history for the Royal College of Physicians Museum. Last month, she travelled north to visit the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow — to explore the archives in person and retrace the quiet, powerful footsteps of the first South Asian medicine women.

As a woman of South Asian heritage, I’ve often found myself standing at the crossroads of multiple identities: woman, medic, academic, Sri Lankan Tamil, and British. Each piece of me informs the other, but they don’t always align neatly. It’s a tension I’ve felt most acutely in the medical field, perhaps because I am one of the first in my family to enter medicine—navigating unfamiliar territory without a blueprint, and constantly asking myself, “What does it mean to be a South Asian woman and a doctor?”

The more I searched for an answer, the more I realized how little information there is about women of colour in the medical profession. The her-stories of these trailblazing figures are often lost at the intersection of colonialism and gender. They’re buried in sparse records or scattered across various institutions, too often overlooked. But I was fortunate. Thanks to the incredible Heritage teams and archivists at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, I was able to dig through the archives virtually—starting my detective work to uncover the stories of pioneering women like Dr. Annie WJ, Dr. Kadambini G, Dr. Rukhmabai R, and Dr. Alice dB.

In March 2025, I made my way to Glasgow, formerly referred to as the second city of the British Empire, to continue this journey in person. It was time to step beyond the virtual archives and walk the very halls where these stories were waiting to be uncovered.

The House of Empire and its Locked Doors

Have you ever paused to consider the doors you pass through? They are more than just physical structures—they shape our experiences, reflect power dynamics, and carry symbolic meaning. Doors can open to safety and opportunity, offering the potential to transform lives. But they can also serve as barriers—constructed from bias, exclusion, and control. Doors only become meaningful through human action; every time we open or close one, we participate in a social act. Doors are never neutral. They embody values, enforce choices, and sometimes, they harm. And when harmful doors dominate, they can shut out the possibility of better ones.

sign is based on those used outside British establishments during the British Raj (source: Channel 4 TV

series, ‘Indian Summers’)

In the British Empire, architecture spoke in the language of power. Doors were not mere barriers — they declared who mattered. Signs like “No Indians or dogs allowed” turned thresholds into tools of shame, etching racial superiority into stone and wood. But exclusion was not only the coloniser’s weapon. Local men, too, guarded entrances—keeping women from temples, from public life, from power. For women of colour, the door was never just closed—it was watched, warned, and often walled shut. Empire and patriarchy worked in quiet accord, deciding who belonged and who did not, who could enter and who must wait. These doors did more than separate spaces—they shaped destinies. And yet, across time, women have reached for handles never meant for them, crossed lines drawn to contain them, and claimed spaces they were never meant to see. In every step across a threshold, resistance lives.

Crossing the Threshold: Women and the Closed Doors of Colonial Medicine

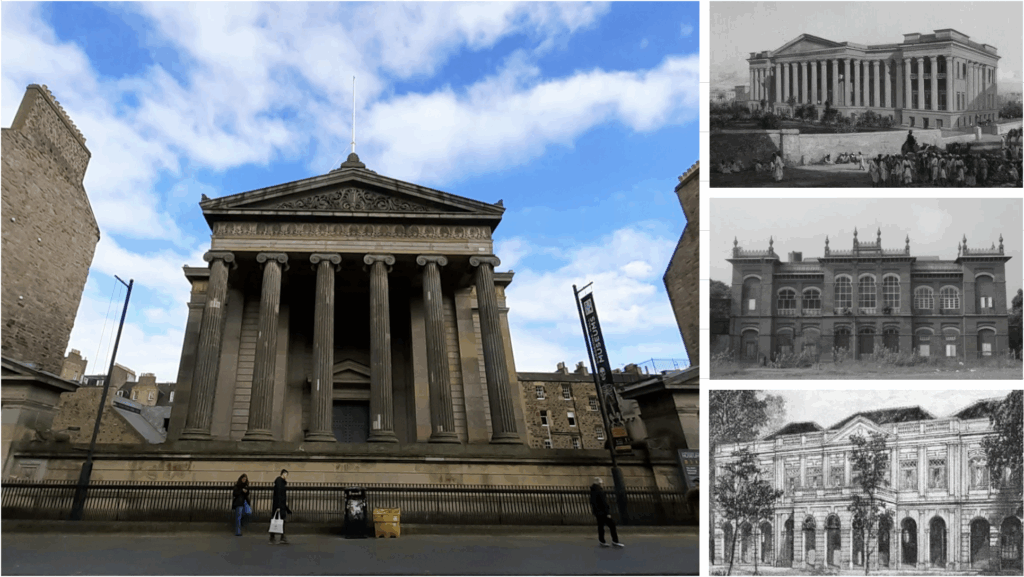

Medicine has its own history of closed doors—wards women were barred from entering or not

allowed to leave, clinical trials that excluded or exploited them, and forms of “care” that masked control. Yet, over time, those doors began to be pried open. The Surgeons’ Hall Riot of 1870 marked a turning point: the Edinburgh Seven—women determined to study medicine—faced hostility and violence as they fought for entry into Scottish medical institutions. In 1875, Madras Medical College became the first in India to admit women students, though they were mostly European. Resistance persisted, and it was not until 1883 that Kadambini Ganguli became the first woman admitted to Calcutta Medical College. Ceylon Medical College followed in 1892.

Calcutta, 1884 (source: British Library Collection: Foster 802). Image right, middle: Madras Medical

College (source: Dorairajan, 2007). Image right, lower: Ceylon Medical College, 1880 (source: Faculty

of Medicine, University of Colombo).

Yet gaining admission did not mean gaining equality. In a society shaped by colonialism and patriarchy, Indian women doctors were rarely granted the respect afforded to White women or Indian men. Denied key responsibilities like ward management, they were relegated to subordinate roles beneath European women. In the community, they were often dismissed as mere midwives, their training and expertise erased by racial and gendered bias. To be treated as equals, many Indian and Ceylonese women sailed across to Britain to seek further credentials — such as the Scottish Triple Qualification (TQ)—hoping that foreign validation might open the doors still closed at home.

From Door to Door: Uncovering Hidden Histories

While in Glasgow, I felt drawn to take my search beyond the archives and into the streets. I walked through Glasgow and Edinburgh, retracing the steps of the first South Asian women in medicine — seeking to understand, even faintly, what their lives might have felt like in these cities so far from home.

Some of the places I looked for had vanished. The residences of pioneers like Dr. Annie Jagannadham and Dr. Kadambini Ganguli no longer stand — one lost to demolition, the other replaced by student housing. Yet not all traces had disappeared. In Glasgow, I found No. 2 Cowan Street, once home to Dr. Jamini Sen, the first woman to become a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (artist: Grace Payne-Kumar).

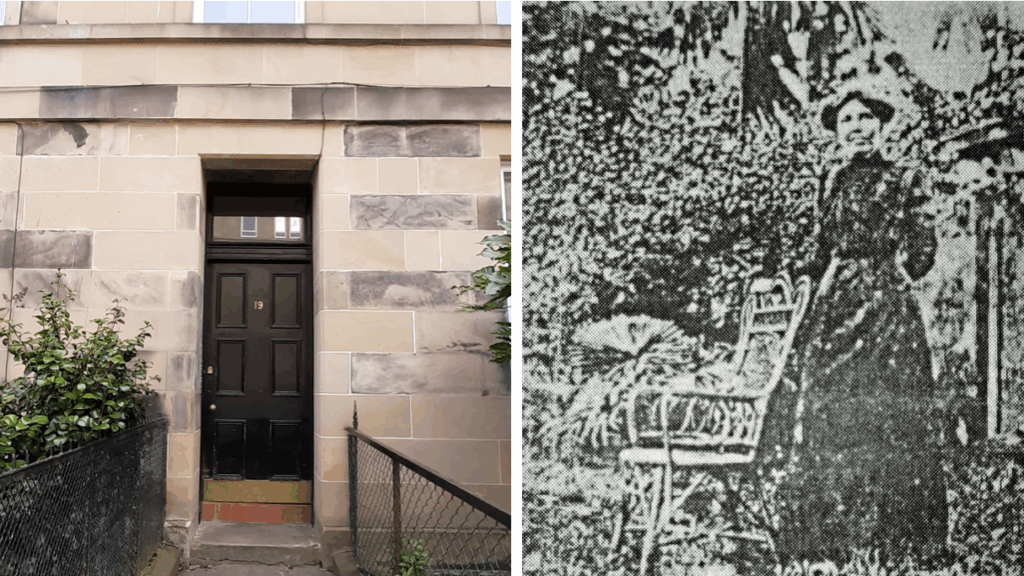

From Glasgow, my journey led me further north to Edinburgh, where more hidden histories waited behind unassuming doors. On Panmure Place, I walked a street once home to pioneering Ceylonese women in medicine. At No. 19 lived Alice de Boer, Sri Lanka’s first woman doctor, who came to Scotland on a scholarship in 1899 and earned her TQ before returning to Ceylon to practise at the Lady Havelock Hospital for Women. Just a few doors down, at No. 13, lived Dr. Winifred Nell, who arrived shortly after Alice and earned her TQ in 1900. She later worked at the Women’s Hospital in Colombo, and at the Leper Hospital.

1994).

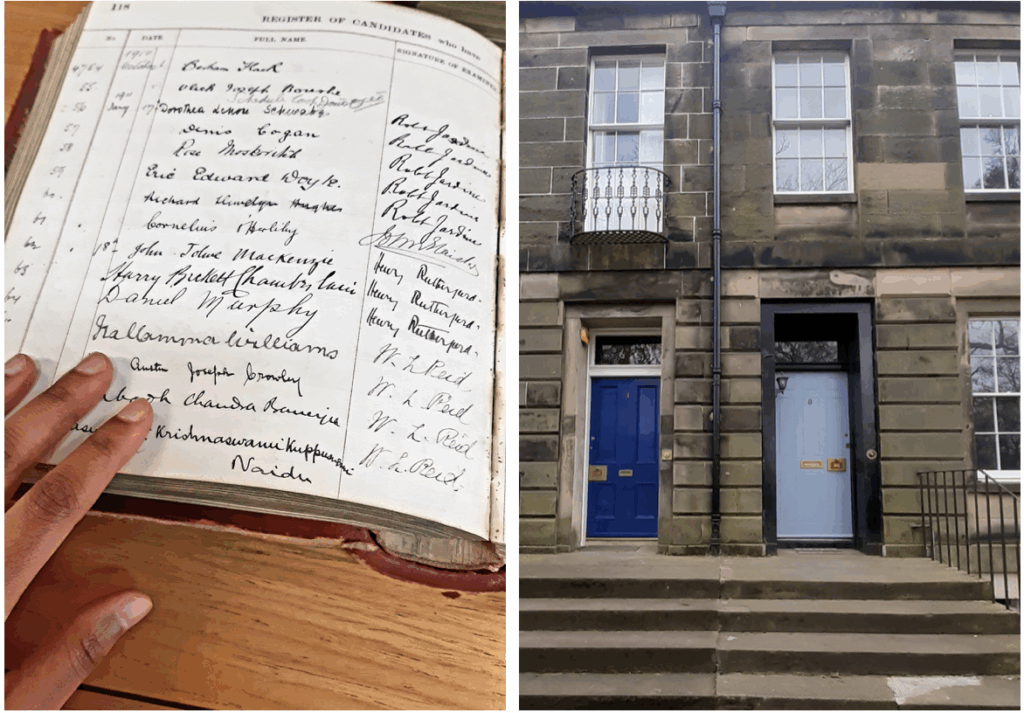

Turning onto Fingal Place, I stepped into the final chapter of my search—a street once walked by another trailblazing woman, Dr. Nallamma Williams. The first Tamil woman in Ceylon to practice Western medicine, she also fought for women’s suffrage. Her name had first appeared to me, nestled within the gold-tinged pages of the RCPSG archives. A century apart, yet there she was —another Sri Lankan Tamil woman, a doctor. Her signature inked in her own hand, defied the silence of history. It was as though the archives had whispered a message of solidarity from the past: You are not the first. You are part of a legacy. No longer did I feel alone.

Surgeons of Glasgow, 1910-1911. Image right: No 3, Fingal Place, Edinburgh, Scotland.

I often think about the doors that led me here. Not just the ones I walked through, but the ones others opened first: a classroom, a university, a hospital. Each one a threshold made possible by grace, sacrifice, and the unseen work of women who came before me. I carry them with me. So when I cross a threshold now, I remember: I didn’t arrive alone.

~ Dr Theeba Krishnamoorthy

Image credit – Banner image: Andy Belshaw, Heather blooms on Ben A’an, Trossachs, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en