Guest post by Sarah Gambell, PhD candidate in Information Studies, University of Glasgow.

Tuesday, 16th of April saw Global History Hackathon enthusiasts from the University of Glasgow make their way to The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow reading room. “Global History Hackathons: Doing Global History through Local Archives and Museum Collections” led by lecturer in Global Economic and Social History Dr Hannah-Louise Clark adapts a format more commonly associated with computer science and technology and applies it to historical thinking and research design. A group of undergraduate students, postgraduates, and professors met together to tackle the themes of global medicine, surgery, and war with the support of heritage professionals Kirsty Earley, Clare Harrison, and Ross McGregor.

Each global history hacker was assigned to one of three teams: Team ‘Bugs’ was assigned the Ronald Ross collection, digging deep into the topic of imperial and international public health. Ross, best known for his work on the transmission of malaria, provided an interesting angle from which to look at colonial encounters involving tropical medicine in the British Empire. Team ‘Bullets’ studied the Archibald Young collection, looking at the dynamics of late Victorian imperialism and medicine. Team ‘Brains’ had their hands on the records of Joseph Schorstein; called ‘R.D. Laing’s rabbi,’ Schorstein’s neurosurgery casebooks had never before been examined by historians.

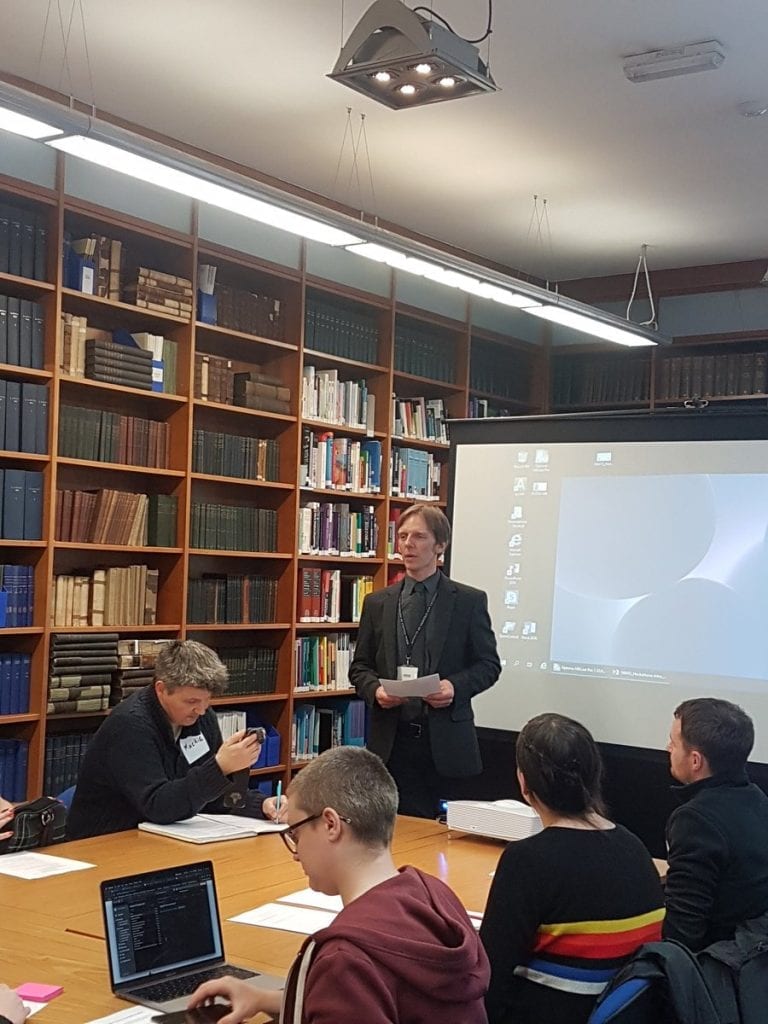

The event kicked off with introductory orientations. First, the hackers received an introduction to the collections and RCPSG by the head of the heritage team, Ross McGregor. Head of team Hackathon Hannah-Louise Clark gave concise and poignant framing remarks for each collection that highlighted the significance of history of medicine within global history: ‘medical history is a history of empire and war-making. It is also the history of world-making.’

Next featured an abridged history of the evolution of Hackathons within the sphere of cultural heritage. This was expertly delivered by POEM associate Franziska Mucha, heritage professional and early-stage researcher in Information Studies at the University of Glasgow. Franziska was able to draw on experience of co-organising her own hackathon in her native Hamburg, ‘Coding da Vinci,’ to introduce the concept.

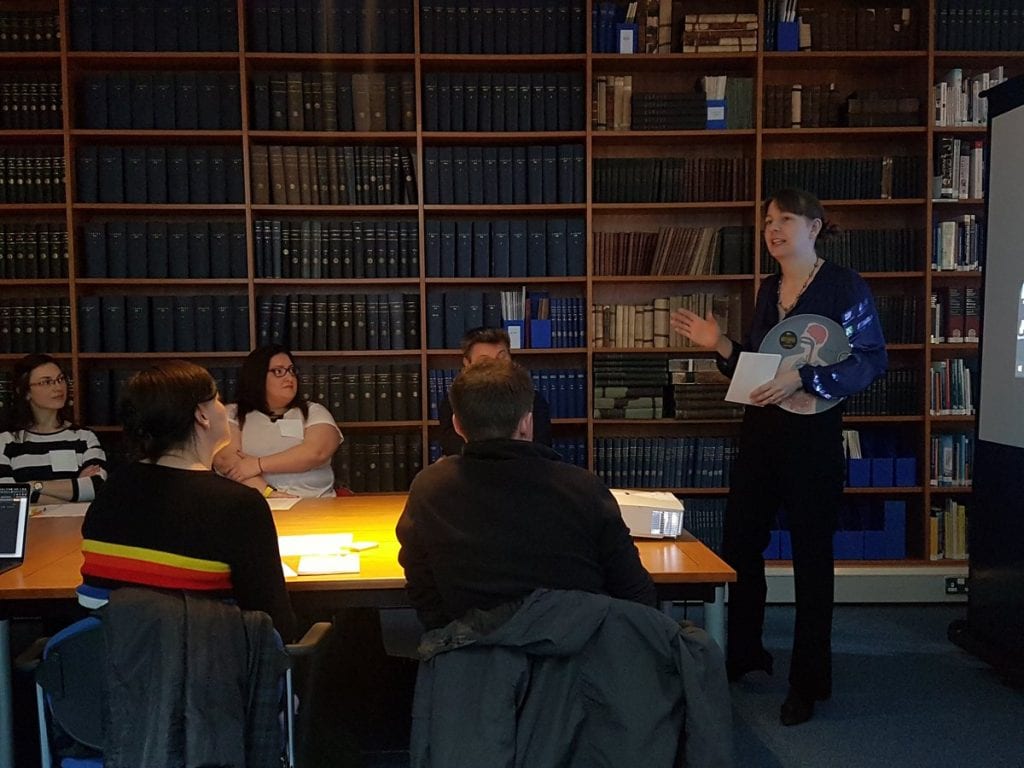

Introductions duly concluded, with hackers eager to set off, the initial brainstorming phase began. Each team was tasked with responding to four questions:

- What global story would you like to tell using these archives?

- How will you use the archival documents to tell this global story?

- What would make this global story more accessible and usable for you?

- What would make this global story more accessible and usable for the people in the places touched by this story?

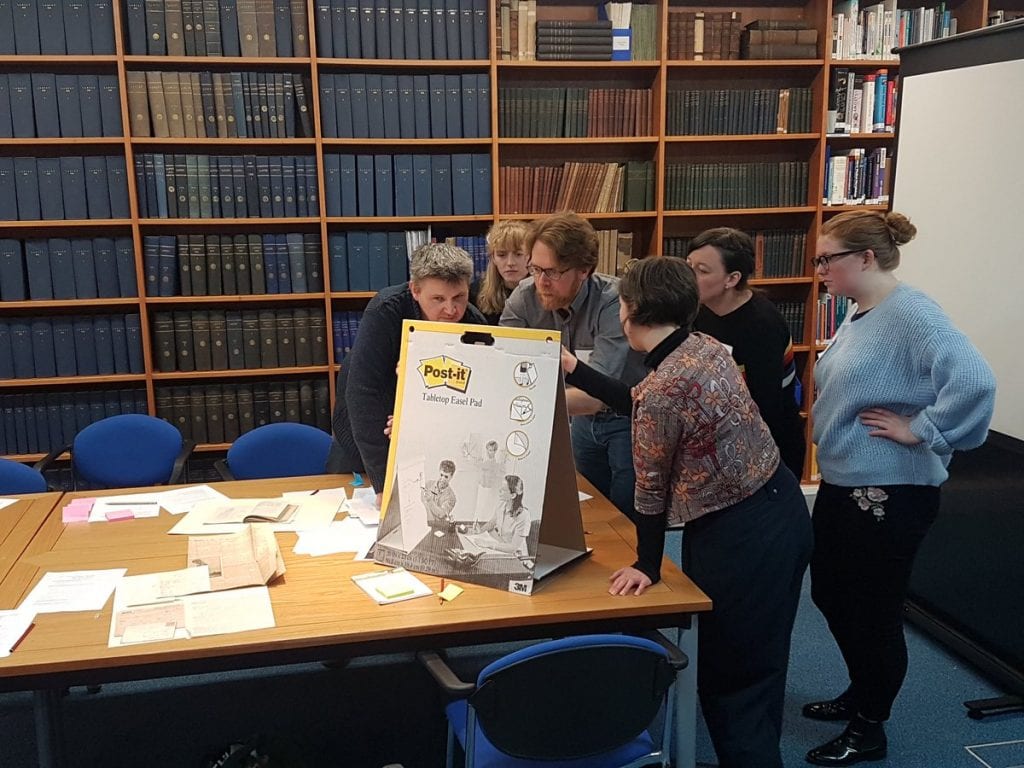

Tirelessly debating the framing questions, each team elected to postpone the break due to the vigour of the discussion; we did not dare pull them away. After the requisite tea and cake pause to foster some less formal analysis, they were ready for the long hack. An hour flew by quicker than any of us had anticipated, and it was, again, a struggle to break up the knowledge exchange.

Results

The final phase of the day’s hack began with presentations from members of ‘Brains’. The only evidence this team had to go on was three of Joseph Schorstein’s neurosurgery casebooks produced in a surgical tent in an unidentified part of North Africa, most likely Egypt’s western desert. Framing the casebooks within the paradigm of human geography, the group envisaged a project that would combine digitisation, data mapping, and medical visualisations. The graphic head wounds recorded in each entry, though morbid in nature, contain much more contextual information than first meets the eye. For instance, it was suggested that the nature and extent of each man’s injuries could be used to better understand the sequence and intensity of fighting during the North Africa campaigns. It was also hoped that making the records publicly accessible would enable information about these soldiers and their postwar lives to be gleaned. Amidst private moments and the scrabble in a WW2 surgeons’ tent, the global history of neurosurgery emerges.

Next was ‘Bugs,’ a multidisciplinary team including a parasitologist, social network analyst, as well as economic and social historians, who had sampled a small fraction of Ronald Ross’ extensive archive. The team was particularly interested in how medical innovation and vaccination were discussed within the collection and tried to contextualise this within the wider context of the British Empire. ‘Bullets’ wanted to use ephemeral records—a list of garments for packing, the running order for a sports’ day, newspaper clippings—to think about ‘local’ South African histories harboured within the Young papers and to amplify the history of African and other non-white participants made invisible by the sources. This team pitched the idea of partnering with a South African institution to open up the collection to a local student or to integrate them into history curriculum packets.

This second hack produced further, intensive focus on a question that had also preoccupied the first: not only positing the question, ‘how do we tell a global story with this local [to us] collection?’ but also, how do we tell inclusive and diverse global histories? How do we ensure that people in the places touched by these collections—and by extension, touched by British imperial and military violence—have access to this information? How might people from Egypt, India, or South Africa access history housed in UK collections and produced with a colonial tilt in the narrative? How can curators be sensitive and post-custodial? How do the non-officer ranks of the British army have their stories told after injury or death? Does this underrepresentation in the recounted history provide an onus for local institutions to make the effort for wider integration in academic settings to raise awareness? That is, are we compelled by this gap to make changes in the future?