Our Artist-in-Residence, Marianne MacRae writes about her introduction to Joseph Lister and her role at the College.

I took up my position as Artist-in-Residence at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow in June and have spent the last month getting a little better acquainted with Joseph Lister. Having come here with only a relatively vague idea of what Lister did to earn him his position as “the father of modern surgery”, I’ve been really keen to read and absorb as many details of his work as possible before I get down to the real “artistry” of the residency.

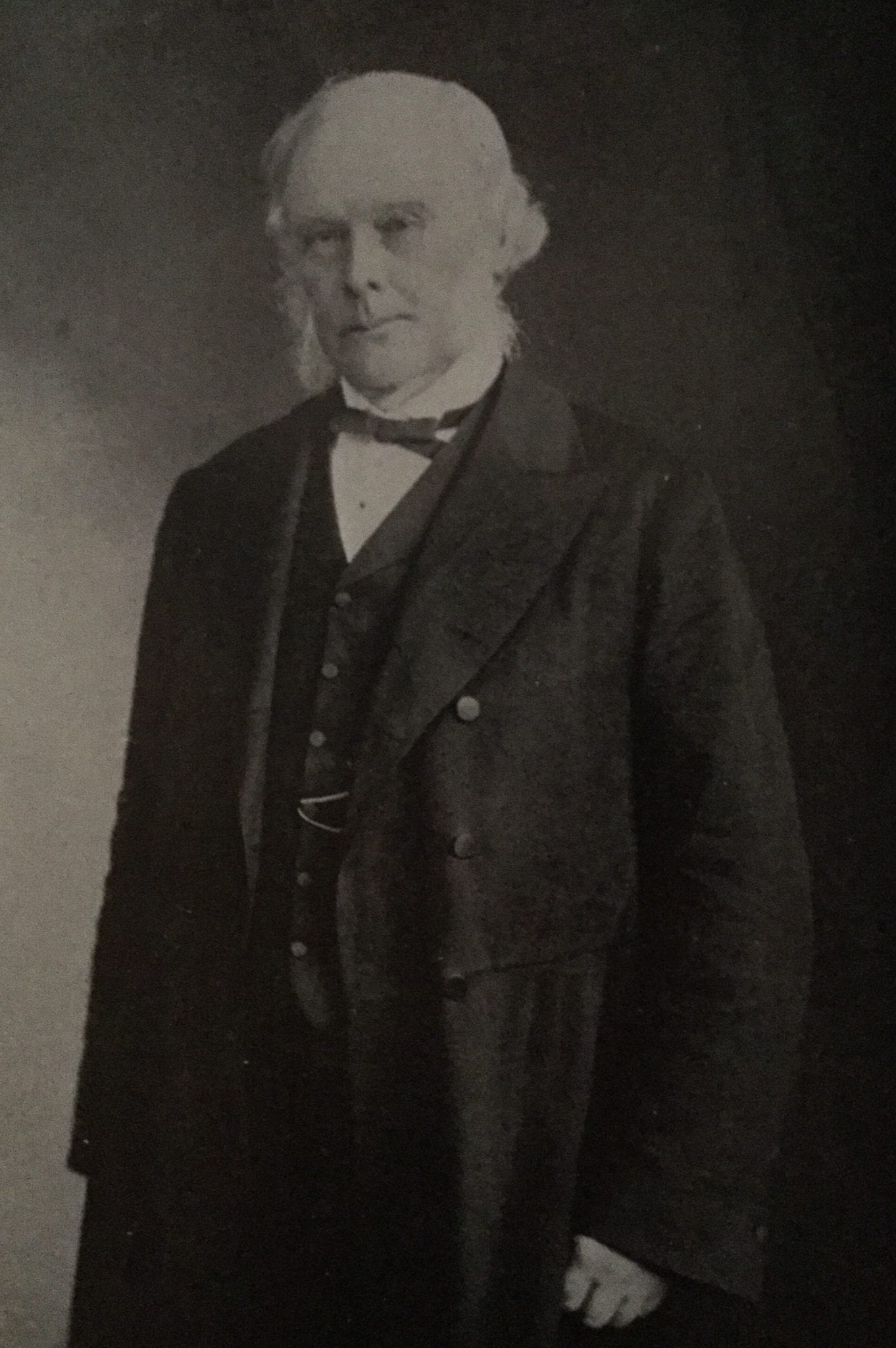

In brief, and for anyone who isn’t aware, Joseph Lister pioneered antiseptic surgery back in the mid-1860s, aka when surgery was the next best thing to a death sentence. Following Louis Pasteur’s pasteurisation experiments, Lister made the connection between germ theory and infection rates in compound fractures (i.e. broken bones that pierce the skin, thus creating an entry point for bacteria). More than half of patients with compound fractures at the time died due to infection. He began testing carbolic acid as a potential solution to the problem, recognising its antiseptic properties after reading that it was used to treat sewage. His experiments were successful and he published his findings in 1867 in The Lancet, which I’ve read and I can tell you there is a lot of detailed pus in those articles, but all necessary in the name of ground-breaking medicine (wouldn’t advise eating, say, a custard tart right after reading though).

Lister promoted the use of antiseptic dressings, sterile surgical instruments and handwashing. His work revolutionised surgical practice and facilitated the aseptic method universally employed by surgeons nowadays. Listerine is also named after him. Overall, a top lad, I’m sure you’ll agree.

My role here

I’m currently doing a PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Edinburgh (don’t hold it against me, Glasgow, I love you both equally), researching animal otherness in the work of Marianne Moore, D.H. Lawrence and Elizabeth Bishop, while also writing my own collection of poetry. So really nothing to do with revolutionary Victorian surgical practices…BUT it does involve a lot of close observation, analytical thinking and, to some degree, experimentation (with words etc.), which is…kinda the same? Hmm, maybe not. Well anyway, I’ll be writing poetry in response to my engagement with the heritage collection here at the college and running some workshops later in the year – more details of those in due course. All this will be specifically in relation to Lister’s time here in Glasgow, which plays an important role in his pioneering work, not least because it was at Glasgow Royal Infirmary that his initial tests on patients took place, while he was Professor of Surgery at Glasgow University.

What have I done so far?

It turns out tuning your mind in to a completely new field of study doesn’t happen quite as quickly as you might think. But here on day 10, I’ve got a few first draft poems that should be ready for human consumption soon, as well as a deeper knowledge of surgery…I mean, don’t hold me to it, but I’m pretty sure at this point, based on my reading of surgical techniques back in the day, I could perform a quick procedure to a Victorian standard. I would even wash my hands before and after, which is more than you could expect from many of Lister’s naysayers. (Please note: I will not be performing any surgical procedures as part of this residency.)

The Heritage team have kindly said I’m free to roam the rooms of the college and spend time getting to know the place a little better. So far my favourite is the Lock Room, which is a v. cosy wee library that has a bunch of Lister-related texts available for perusal. It also has, to my mind, the funkiest carpet (see above) though the tartan of the Alexandra Room is also quite impressive.

I’ve spent some time familiarising myself with some of the socio-historical factors that were pertinent at the time. I’ve been particularly taken with Thomas Annan’s photographs from the period, which document the horrendously impoverished conditions that the working class people of Glasgow were living in at around the same time Lister was making his discoveries. I’m currently working my way through a book called Midnight Scenes and Social Photographs: Being Sketches of Life in the Streets, Wynds, and Dens of the City of Glasgow (bit of a mouthful), which offers an account of life in the tenements. The writer, known only as “Shadow” (v. mysterious), is certainly not the most sensitive of documentarians and the people he describes are often dehumanised to a disgraceful degree. At the same time though, it offers an interesting insight into the lives of the poor, which are too often written out of history altogether. I’d really like bring these people back to life somehow, and will be working on a way to incorporate this in to the scope of the project.

Finally…

I’m really excited to be here! It’s amazing to be given the chance to write about such an interesting period of change in Scotland that had a worldwide resonance and recapitulated the way we approach not only medicine, but personal hygiene and sanitation. That we can divide the history of medical discoveries into “before Lister” and “after Lister” is a testament in itself, so I’ll be working really hard over the coming months to do his story artistic justice.

[…] Royal Colle4ge of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow: Our Artist in Residence “meets” Joseph Lister […]